Most of us grow up with strong influences from our culture’s mores for positive behavior. As adults who are writing stories that include a range of characters, we must at times imagine the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that we have been trained to consider as negative or wrong—especially when creating villain songs.

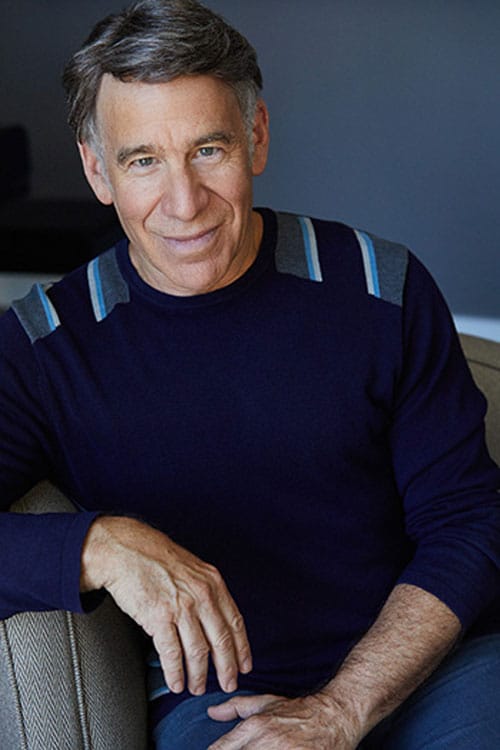

Stephen Schwartz, musical writer for stage and film (Godspell, Wicked). Credit: Nathan Johnson

Just as actors may relish playing villains, some writers find it refreshing to imagine life from inside a mind they might consider evil. Stephen Schwartz (Godspell, Wicked) has often expressed how much he loved writing lyrics for “Hellfire” for Claude Frollo, the villain of The Hunchback of Notre Dame musical (animated feature and stage adaptation).

Knowing this, as soon as I heard the new Alan Menken/Stephen Schwartz song “Badder” while watching the Disney+ movie musical Disenchanted, I wanted to ask Stephen about writing songs for villains or antagonists. Although we had touched on this during interviews for my book Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to Wicked, conversing about “Badder” and villain songs from a musical writers’ standpoint seemed like a fruitful idea.

Villains in Musicals

Carol de Giere: Would you say that villains are the characters who thwart the protagonist’s desire, their want? Some kind of adversary in every case?

Stephen Schwartz: I think not every antagonist is a villain. But every villain is the antagonist. Not every musical has a villain, and I personally have only written a couple where I would say there’s an actual villain in the show.

Knowing we were going to speak about this, I gave some thought to it, trying to think of villain songs in other musicals. I went back to one in which the bad guy knows he’s a bad guy: “Those Were the Good Old Days” from Damn Yankees, sung by the Devil, in which he’s talking about how much fun evil was in the past. It seems to me that’s a quintessential villain song in the classic sense of “mustache-twirling” villain. It’s of course a comic song, as many for self-aware villains are. Captain Hook’s song “Hook’s Waltz” from Peter Pan also comes to mind, and maybe “A Simple Little System” from Bells Are Ringing. All three of these examples feature villains who know what they are, and all three of them are a lot of fun theatrically.

Thinking of my shows, The Magic Show has a villain—the older magician. His songs were also intended to be comic. And both Disney animated features that I worked on had outright villains, as cartoons tend to do. In Pocahontas it is Ratcliff. His first song is comic: “Mine, Mine, Mine,” but then he leads a song later on—“Savages”—that is not comic at all, but a display of racism, which of course is thematic to that story. And then there’s my favorite, which is Frollo from The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and “Hellfire.” That’s an example of the more psychologically complicated villains—villains who don’t know they’re villainous – which is I think truer of real-life villains.

But then think all the way back to Oklahoma! and what Oscar Hammerstein II wrote for the character of Judd Fry when he wrote “Lonely Room.” Considering when that show was written, one might have expected a very different song. It could have been an outright “I’m-the-bad-guy” villain song, but Hammerstein chose to make him psychologically complex, to write him so the audience could see things from his point of view and develop a certain kind of sympathy for him.

Why Include a Villain Song?

de Giere: One of the things I wanted to ask is why are villain songs valuable? Someone has said we’re stepping into the experience or point of view of the villain. Jack Viertel in The Secret Life of the American Musical (page 122) says, “Generally speaking, villains are most compelling, when, however terrible they are, we’re forced to understand their point of view.”

Schwartz: I think that’s well put. Frollo is to me a prime example of that.

de Giere: In West Side Story there’s the song “A Boy Like That” that Anita sings. She is trying to put a stop to Maria’s intentions.

Schwartz: I wouldn’t call Anita the antagonist in that show by any means, although at that moment she is antagonistic to what Maria wants to do. We understand her point of view, and she’s coming from the best of motives.

Villains are self-interested, and whatever they are doing is in service of getting what they want. I think that’s sort of the definition of a villain. Therefore, a character who may be an obstacle to the protagonist—but whatever he or she is doing is from a different kind of motivation—they can qualify as antagonists but not as villains.

de Giere: In West Side Story, it’s almost the situation.

Schwartz: The villain is society—the gangs are victims of their circumstances, as in Romeo and Juliet.

Song Spotting

de Giere: Is there anything you can say about song spotting the place for a villain / antagonist song – like was there any challenge in finding where “Wonderful” would go in Wicked?

Schwartz: Not really, no. I think my inclination is to put them later, after you’ve gotten to know the character a little. But often, especially in animation, the song is more-or-less the introduction to the character. Ursula’s “Poor Unfortunate Soul” in Little Mermaid comes early, and “Gaston” in Beauty and the Beast does too, though it’s true both characters have had brief scenes previously. Ratcliff’s song “Mine, Mine, Mine” is basically his introduction.

I think if you’re just trying to establish who is the villain or the antagonist, and what does he or she want, and how is that going to be an obstacle to the protagonist, then the song comes pretty early. If we know that this is the antagonist but now we want to give them more dimension or nuance, then it will come later. “Wonderful” comes later and “Hellfire” comes later.

Structuring Villain Songs – “Hellfire”

de Giere: So, let’s look at structuring a lyric. Is there anything you can say about how you decide the journey within villain songs? Does it just depend on the job of the song?

Schwartz: I think there’s no difference between writing a song for the character who might be considered the villain or the character who might be considered the hero or heroine. You’re still asking what does the character want? What’s the job of the song?

In “Hellfire,” Frollo is very uncomfortable with the feelings inside of him and feeling great shame and guilt about them, which, being a narcissist, he is not able to handle. Therefore, what he does is project: ‘It’s not my fault. It’s her fault. And so these things that I’m feeling I’m going to blame on her.’

de Giere: Are you saying that when you structured Hellfire, the first thing you did was to have him explore his own psychology, and then the projection, so that becomes a journey of the song.

Schwartz: I didn’t think of it in such programmatic terms, but I gave a lot of thought to his psychology and how he would behave. I think I’ve cited to you before a book by M. Scott Peck called People of the Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil, which was very influential on me. It’s a psychological definition of evil. What Peck had to say about how he defined evil behavior – that evil is essentially imposing one’s will on another person—I found very compelling and drew upon that psychologically to become Frollo. And I say to “become” Frollo rather than “write” Frollo because I don’t really write from outside in. Certainly with that song I didn’t.

de Giere: You found the place inside of you.

Schwartz: And then wrote down what that was.

My favorite character I have ever written is Frollo, who is probably the most despicable human being in anything I’ve done; I love him as a character. He was so totally self-justifying and in such denial of his own true motives. It was really fun to go to dark places in myself I would never let myself do in real life. It made me understand why actors love to play villains.

~ Stephen Schwartz

de Giere: You’ve talked about Puccini’s Tosca as inspiring the music for “Hellfire.”

Schwartz: Well, it’s not the music – which is of course completely Alan [Menken]’s own – but the concept. At the end of the first act of Tosca the villain, Scarpia, is at Mass and he is thinking about how he is going to make Tosca his own. In the background the Mass is going on – the ‘Te Deum.’ When writing “Hellfire” I was basically thinking– let’s do that, but let’s let it be the ‘Confiteor’ and have the whole thing be a confession, but instead of confessing his own sins, Frollo is going to say – I’m not guilty, it’s her fault, not me. He’s going to do the opposite of what a confession is supposed to be.

A few samples of “Hellfire”:

A cappela cover

Patrick Page on the studio cast album

Villain Song Example: “Badder” from Disenchanted

SPOILER ALERT: If you haven’t yet seen Disenchanted and want to read about this example, ideally see the movie first (Disney+). Or enjoy the sample below.

de Giere: I wanted to focus on “Badder” as an example, since you wrote it fairly recently.

Schwartz: “Badder” is an unusual song because it’s two villains. This was more inspired by those two-women-trying-to-top-one-another songs. like “Bosom Buddies” from Mame or the “Jealousy Duet” from Threepenny Opera. Neither of those are villain songs. But in the story of Disenchanted, both characters are aware they’re villains at this point, and each wants to be a greater villain than the other. They’re in competition. So consequently the title—which is what I came up with first, as I frequently do—“Badder.” I like it because the word doesn’t exist in English.

de Giere: Did you do it in one draft?

Schwartz: No. Things got rewritten. The director (Adam Shankman) kept changing the scene that led into the song, so I had to make adjustments. But the basic idea never changed.

de Giere: I was curious about the garter snake and Puff Adder: did you use a rhyming dictionary? Or did that come into your head?

Schwartz: Not in this case, though I frequently do use a rhyming dictionary to make sure there aren’t any good rhymes I haven’t thought of. But in this case, I was trying to think of funny words that rhymed with “badder”, or words that could be put in a funny context, and I thought it was funny for someone to brag about themselves, “I’m like a puff adder.” And therefore, in comparison, she would put down her competitor by comparing her to a less deadly snake – a garter snake. Another funny rhyme was “bladder,” so of course I had to get that in there too.

And since this part of the movie is intended to be a spoof of animated fairy tales, there are a lot of references in the song to other fairy tales and how the villain is disposed of.

de Giere: And this one you’re associated with: “Maybe there’s a house you can drop on her.”

Schwartz: Exactly right – I had to get Wicked in. And there had to be a reference to all those other Disney cartoons, where villains are always falling off the roof to their death — including in the original Enchanted.

de Giere: So, you’re just coming up with these things – do you make a lot of notes?

Schwartz: Sure. I just made lists, such as what other villains could I mention? We wound up with Maleficent and Cruella. Originally Jafar was in there, but I decided it should be two female villains, so he didn’t make the cut.

de Giere: And then you made a list: climb the bean stalk, or go down the rabbit hole, poison apples…

Schwartz: Yeah: what are things that happen in fairy tales? Since the whole point of Enchanted and Disenchanted is you’re in a fairy tale world, all the references should be to fairy tales, and especially Disney fairy tales: Or I guess to put it more accurately, fairy tales of which Disney has made animated movies.

de Giere: Then we’re headed toward the final lyric “Very, very baddest of them all.” You’ve talked before about how you head into the ending of a song.

Schwartz: This is a very standard-structure song. It’s basically verse, chorus, 2nd verse, 2nd chorus, bridge, and extended last chorus. In that extended chorus, there’s a triple rhyme which helps build to the end – a technique I’m probably overusing at this point. And it seemed pretty obvious that in a song called “Badder,” the last line had to contain the word “baddest”.

Last chorus from “Badder” – lyrics by Stephen Schwartz, for Disney’s Disenchanted:

Both: Once I sit alone

Atop the villain ladder

Everyone in Monrolasia

Will totally be in my thrall

They will say

“Oh, Queen, we praise ya”

Giselle: Because I will be not just badder

Malvina: Because I will be not just

Both: Badder, badder

Malvina: But the nasty

Giselle: Everlast-y

Both: Flabbergast-y

Very, very baddest of them all!

Stephen Schwartz and Carol de Giere enjoy a lively and insightful discussion of villain songs

I loved this article, the musical examples used, and your reference to M. Scott Peck’s “The People of the Lie.” I had read that book decades ago, and it never occurred to me to use that info in the development of my villain! Thank you! I don’t think it’s too late for me to flesh him out a bit better.