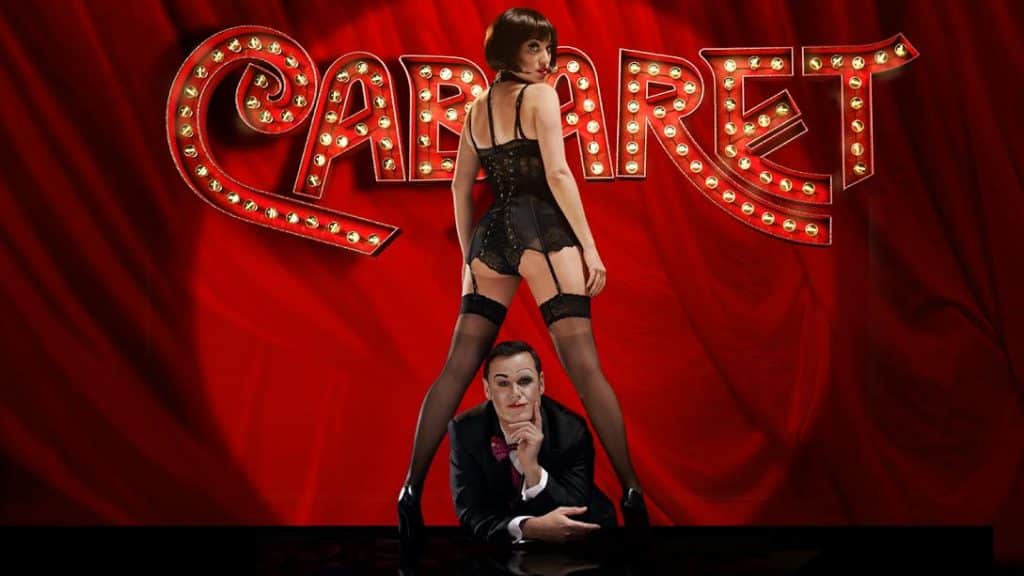

Cabaret is a very seductive musical with familiar-sounding and attractive songs. The first five notes of the title song are also the first five notes of “Put On a Happy Face,” and while everybody seems to think this was literally unintended, the effect is certainly what the creators were after. 1930 Berlin is meant to feel recognizable to us, the typical American musical comedy audience. So, the songs are very conventional, even if the composer utilizes a certain amount of Kurt Weill-like flavor. In its insinuating way, Cabaret lures us into its world, until we find ourselves identifying with characters who, more or less, become responsible for the rise of Hitler.

The protagonist is a lot like us: American, totally naïve, and not at all conversant in the ins and outs of European politics. He is drawn to Sally Bowles and the glittering and sexy cabaret world like a moth to a flame. And so are we. In the score’s richest song, he admits to being in a “euphoric state” and asks “When you’re enchanted, why break the spell?” Our hearts agree with him while are heads say we should be cautious, because we know to fear the Nazis. Cabaret effectively dramatizes this conflict between heart and conscience.

Like many a traditional musical, Cabaret presents two couples: Cliff & Sally and the more comic subplot of the landlady and the Jewish grocer. Funny as the subplot is, we’re well aware of the tragic implications: 1930 Berlin is a bad time and place to be Jewish. We want all the characters to escape from Germany so they and their love can live and grow, but, for various reasons, the characters aren’t brave enough to escape. Our natural expectations that love will win out in a musical are subverted.

This was pretty bold stuff in the second decade after World War II; it must have seemed a pretty unlikely subject for a musical. Today, musical authors take on dark episodes from history all the time. But no musical tragedy since has had the same amount of truly entertaining comedy that can be found throughout Cabaret. Unfortunately, writers who imitate its bleakness forget that it’s the laughter and glitzy showmanship that make such a message palatable to an audience.

Commentary and writing tips by Noel Katz