Ready to geek out on composition analysis? Musical dramatist and composer Robert Vieira breaks down theory and thoughts on one of the most (ahem) popular musical theatre scores in history—Stephen Schwartz’ masterpiece: Wicked.

Analyzing the Wicked Score

In February 2005, the Wicked original cast recording received a Grammy® Award for Best Musical Show Album. The question arises, how is Stephen Schwartz’s score so successfully dramatic? I believe part of the answer lies in the use of what I’ll call “breaks and links.” Wicked’s score is groundbreaking because it represents a new level of melding pop idioms with sophisticated musical theater song construction. The frequency and dramatic density of Wicked’s score’s breaks and links is one way to describe this achievement.

The many “breaks” in the songs of Wicked serve plot advancement and character transformation by “breaking” tonality and tempo. Sections marked “Freely” in Wicked’s Vocal Selections identify some of these breaks. By moving Wicked forward, breaks prevent the application of dramatic brakes. They moderate the drama’s metabolism by speeding it up, slowing it down, moving it toward speech, and pushing it toward money notes. Stephen Schwartz’s “Note from the Composer” in the Vocal Selections mentions the process of extracting the show’s songs from their dramatic context—this entailed removing many breaks and links which make no sense in stand-alone versions of songs.

Counterbalancing the breaks in the score are the performance decisions and lyrical/musical links that unify Wicked. In addition to listening for breaks, we will examine the deft use of such links. The combination of breaks and links is how Wicked‘s score supports the needs of the libretto. Stephen Schwartz never sacrifices drama for the conventions of songwriting. The whole organization of Wicked’s score—both in terms of song structure and the alternation of song types—supports drama because it is a score, not a collection of pop tunes. Wicked‘s music might be described as “folk/pop-influenced,” but it wildly transcends those styles. For all these reasons, I’ll analyze the score independent of any particular lyrical or musical style.

The following aspects of musical theater will guide our examination: harmonic dynamism, non-diatonic melody writing (to color lyrics), the structural handling of recitative, and the use of leitmotivs and lyrical links. Breaks crack open a song’s structure and accommodate verse-intros, dialog, parlando, and colla voce passages. Melodic and lyrical links serve the dramatic purposes that lead to the breaks in the first place. All these technical aspects help us to take things apart and see how the machine works, but analysis is a fool’s errand without constant attention to how everything comes together to make a show work. I will, therefore, comment on the purely dramatic and performance aspects of the scenes as captured on the recording. Winnie Holzman, Gregory Maguire, William David Brohn, Joe Mantello and others contributed to the success of these dimensions. I will also examine Schwartz’s songs in their presentation sequence, rather than organizing this article by analytical categories. Wicked’s songs comprise an ordered evening of entertainment and we must respect the Wicked score’s integrity.

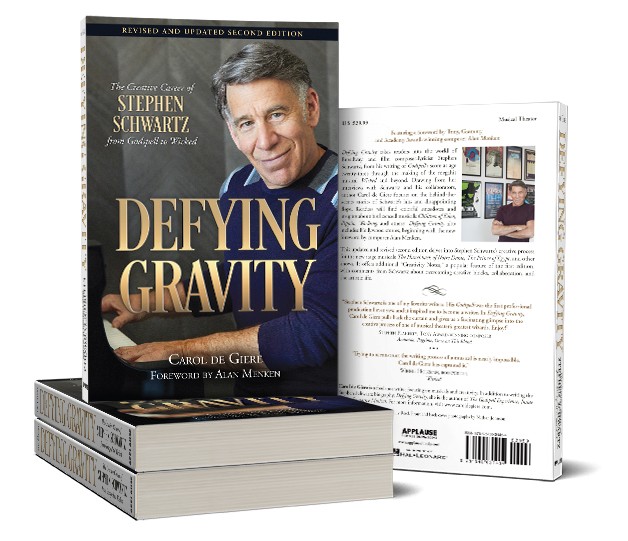

Wicked composer Stephen Schwartz in his New York studio, 2018.

Act One of the Wicked Score

Track numbers refer to the Original Broadway Cast CD

Track 1: “No One Mourns the Wicked”

From the opening moments of Wicked, we hear a vital structural ligament of the score—what might be called the “Wicked Witch Theme.” As Carol de Giere explained, [Wicked‘s Musical Themes (external web site)] this six-note leitmotivis a link that comes from the opening accompaniment figure that runs through “As Long as You’re Mine.” In a slightly modified form, this accompaniment texture begins the mini-overture that comprises the first minute of “No One Mourns the Wicked.” This leitmotiv captures both the essence of Elphaba’s fearsome aspect—which is a creation of the citizens of Oz—and the dark, romantic setting of Elphaba’s doomed love affair with Fiyero. Of course, the audience does not yet realize that this leitmotiv also foreshadows Elphaba’s self-doubts and the hysteria of a land where good and evil are not so clearly separated as Ozians believe.

The complete dramatic structure of “No One Mourns the Wicked” can only be appreciated after experiencing the complete score—so we will return to this bookend song at the end of our tour. At this point, let us notice just a few powerful moments. First, when Ozians express their glee and relief at the death of the wicked witch, Schwartz culminates this section by setting the final “good news” on a key change (1:28). Second, after “No One Mourns the Wicked” moves back in time by way of dialogue and other breaks (3:35), the “Wicked Witch Theme” returns to bridge past and present. The audience will not discover the origin of this leitmotiv until near the end of Act II, but here—as Elphaba is born—we encounter a crucial instance of this theme (4:54). From the first unwelcome moments of her life, Elphaba elicits fear and loathing. With a skillful use of underscoring, Stephen Schwartz tells us Elphaba is in for a difficult life. She will be rejected by her parents, her fellow students, one potential lover, and the vast majority of Ozians.

The harmonic ambiguity and versatility of the “Wicked Witch Theme” allows it to support both Elphaba’s troubled birth and her short-lived but intense love affair with Fiyero (“As Long as You’re Mine”). If we need more proof of the resonance between Elphaba’s ill-fated birth and her later doomed love affair, we need only listen to the two-measure musical buildup before her birth (4:46) and the nearly identical buildup before her rueful decision that good deeds must always be punished (2:25 of “No Good Deed”). Elphaba’s leitmotiv represents the theme of Fate in Wicked: witches who are born looking like ferny green cabbages will be deemed evil; good deeds performed to get attention will carry a karmic backlash. Elphaba hopes the Wizard won’t be blinded by her looks, but Fate is powerful.

The Wicked score uses of the “Wicked Witch Theme” to symbolize Fate reminds me of Bizet’s use of the spine-tingling leitmotiv associated with the title character in his Carmen. First appearing at the end of the opera’s Prelude, Bizet’s non-diatonic leitmotiv shares two traits with Elphaba’s theme: it’s never set to lyrics and it symbolizes both a character’s ominous persona and her ill-fated love affair. Carmen’s theme reappears as light sixteenth-note flourishes in Carmen sur tes pas (Act I, scene 6) as Carmen flirts with a group of men and selects Don Jose; it then assumes its original, dark form as Don Jose ruminates on how Carmen threw a flower at him like a dart. In the volcanic conflict scene where Don Jose tells Carmen he has to get back to his soldiers (Je vais danser en votre honneur, Act II, scene 17), the theme tolls as the same flower is pulled from the corporal’s vest. At the opera’s end, Don Jose has killed Carmen in a jealous rage and the Carmen leitmotiv both explains and comments on the murder. In both Carmen and Wicked, a brief leitmotiv represents the bestial charm and dark power of a captivating, but ultimately tragic woman.

Toward the end of this opening number, Glinda brings us back to the present time (5:23). The chorus celebrates, while the Good Witch is conflicted (for reasons that are not clear yet). As the Greek Chorus reaches its dramatic peak, “No One Mourns the Wicked” ends with an ominous Picardy third (6:23). The title of the show is declared with a G# on an E-major chord, emerging out of a song that is at that point in E-minor. This move to the parallel major would normally convey a happier, brighter moment, but in the topsy-turvy world of Wicked, nothing is that simple. The boisterous G# of “Wicked!” embodies the self-righteousness of Ozians. They are prone to confuse surface with substance;the sudden change to E-major is imbued with all the shallowness of Oz’s conventionality.

Track 2: “Dear Old Shiz”

After Galinda denies her friendship with Elphaba, the show goes back in time and stays there. The ubiquitous “Wicked Witch Theme” introduces the student song (0:30-0:34). Thus, a leitmotiv links the show’s opening tableaux with the educational institution of Shiz—the very place where Elphaba’s ostracization begins and where her loathing of Glinda takes root. Even after Glinda and Elphaba are best friends, Fiyero will come between them, and this love triangle’s musical expression is the link of the “Wicked Witch Theme.”

In the tapestry of Schwartz’s choral arrangement (he did his own arrangements on this song), we hear the façade of school life. The strict Protestant harmony expresses both the shallowness which breeds Elphaba’s cynicism and the group-think that feeds Galinda’s thirst for attention as her persona takes flight. This chorus number is a dramatic complement to “No One Mourns the Wicked.” At Shiz, young students are hopeful about the future; the older chorus of “No One Mourns the Wicked” remains hopeful, but only because the Wicked Witch is dead. The origin of the conventional cruelty of “No One Mourns the Wicked” and its sanctimonious “Goodness Knows” theme is found here, in the shallow solemnity of rule-bound Shiz.

Track 3: “The Wizard and I”

In the Wicked score, “The Wizard and I” admirably fulfills the function of the “I Want” song that is at the heart of most successful musicals. Despite being the show’s third number, it is really the second song of Wicked, in conformity to the “second-song-is-most-important” theory of musical theater (“All I want is a room somewhere…”). As Wicked was evolving, Stephen Schwartz and his son, Scott, put their directorial heads together to find the right place for this song. Along the way, very funny scenes at Shiz had to be sacrificed to maintain dramatic momentum and metabolism.

The first part of the verse-intro (0:01-0:46) establishes the dramatic element of Elphaba’s longing. Madame Morrible entices the young green witch by suggesting the Wizard will want a meeting. Elphaba then expresses her desire to be good (0:52-1:17) in the only part of the verse-intro that appears in the solo version published in the Vocal Selections.

As the song proper begins (1:17), its pulse, melody, and arrangement are influenced by an accessible pop style—yet, at the same time, “The Wizard and I” is completely organic and powerfully dramatic. Its many breaks support essential transitions in Elphaba’s internal state. They highlight moments of recitative as we arrive at all the points of Elphaba’s dramatic evolution. She doubts, wishes, imagines, predicts, exalts, declares. Let’s visit each point on the arc.

The Wizard and I” admirably fulfills the function of the “I Want” song that is at the heart of most successful musicals. Despite being the show’s third number, it is really the second song of Wicked, in conformity to the “second-song-is-most-important” theory of musical theater…

At the half-way point of the first statement of the A-section, we get a parlando break with the spoken “since birth” (1:35), leading to a potent use of non-diatonic melody writing. As the lyrics describe the blindness of Ozians and the small-mindedness of Munchkins, we get non-diatonic Bb’s (Flat 7 of C major). Then the word “see” is set on the first B-natural of the whole section (1:52). This begins Elphaba’s imagining what the Wizard will say to her—unlike all the others, he will see who she truly is and the music’s alternation from Bb to B-natural makes Elphaba’s faith crystal clear. The holding back of the leading tone until this point is electric. The whole scheme is repeated later when Elphaba asserts Oz will have to love her (Bb’s) for what “I have inside” (B-natural). We find a similar non-diatonic mechanism in “Dancing Through Life” as Fiyero contrasts hard reality with sloughing off. Schwartz successfully colors lyrics through non-diatonic writing that remains smooth and appealing.

We encounter the shimmering B-section of “The Wizard and I” as Elphaba imagines meeting the Wizard and hearing him commiserate on the superficiality of Ozians (2:46). Here at the più mosso break, the tempo quickens and the harmony thickens with sparkling 9th‘s and 11th‘s. The score flirts with another key, then returns to the B-natural in the melody as Elphaba declares the Wizard will see she is “so good inside.” The Bb’s again march on stage when Elphaba-as-Wizard sings about the “folks” of Oz and their absurd fixations on the superficial. Elphaba then admits to her own vanity in a magical bit of writing and singing (3:19): on the first B-natural in a while, we hear Elphaba claim that being degreenified is not important to her—a claim she immediately forsakes.

In another powerful break, the orchestration thins, the key jumps down a major third and the pulse slackens as Elphaba expresses her deep-seated conviction that she is “Unlimited” (3:35). A second break for a recitative moment allows Elphaba to admit she has a crazy, hazy vision (3:55), culminating in the vital prediction by the ferny cabbage that one day there will be a celebration “all to do” with her (4:09). Elphaba’s longest held non-song-ending note in the score then sets up the triumphant final section, distinguished by two rallentandi (4:18, 4:49) and a thinning break in orchestration (4:41), all of which emphasize the solidarity Elphaba feels with the Wizard. Oz’s favorite team has taken life in Elphaba’s mind.

Elphaba’s prediction of a celebration becomes a strategic link: in “Wonderful,” the Wizard will dazzle Elphaba by dangling before her eyes the fulfillment of this heartfelt wish for public acceptance. Fate, of course, stands in the way.

We cannot leave “The Wizard and I” before noticing the performance decisions that led to Idina’s astounding diphthong transitions and word finishings; they are sonically clear and appropriate to the character. “Esteem” sounds exultant and angry (4:42); the ending belt of “I” resonates with all the exploding élan of Elphaba.

Track 4: “What is This Feeling”

“What is This Feeling” was the fourth re-write for this moment in the show. Schwartz first came up with a semi-patter song about the school business (which was cut when the longer school scene was deleted). Then he wrote a Viennese waltz for the current lyric, and a more angular setting that sounded like a Munchkin vaudeville when he played it in his midtown apartment. Only while he was playing that number in one of the workshops did Schwartz say to his producer, “You’re right, the energy dies, and I know what to do about it.” “Loathing” is what he did about it.

This song’s verse-intro is an excellent handling of recitative—of material that needs to live in the world between non-musical dialog and full-blown song lyrics. The charming intro also connects the separate playing areas of the two actresses on stage.

Although the main theme sounds too smooth to be non-diatonic, a powerful break from tonality makes it distinctive. The phrase “Ev’ry little trait, however small” is set to the score’s baldest IV-V-I cadence (1:25), but Schwartz follows this up with a mirror cadence—transposed down a major 3rd—to set “makes my very flesh begin to crawl” (1:28). We came across this same contrast-oriented non-diatonic writing in “The Wizard and I,” and we will encounter another example in “Dancing Through Life.”

The rest of “Loathing’s” structure in the Wicked score accommodates several breaks and beautiful woven vocal lines. The chorus breaks in (1:56), Galinda breaks back in to complete the “bias/try us” rhyme (2:08), and then the chorus ushers in two key change breaks (2:26, 2:49) as the song declares an apparently unbridgeable rift between the two witches. [Can you figure out the odd sound after “last” in “still I do believe that it can last” (3:07)? It remains mysterious to me, despite 68 listenings.]

Track 5: “Something Bad”

Opening with the exact same spoken phrase as does “The Wizard and I” (“Oh, Ms. Elphaba….”), “Something Bad” clearly shows that Elphaba is being seduced by Morrible and warned by Dr. Dillamond in the same manner—but from opposite ends of the evil-good spectrum. A great performance decision led Idina to deliver the spoken line “That’s why we have a Wizard” (0:58) in a natural, organic, concerned, and believable way.

Even before it begins to dawn on Elphaba that all is not well in Oz, we get a very important leitmotiv link. After a descending line in the bass clarinet, we hear Elphaba declare (1:21), “It couldn’t happen here,” set to the same musical phrase that is used for “I hope you’re happy now” in the verse-intro of “Defying Gravity.” Elphaba’s shaky declaration in “Something Bad” encapsulates the hopes and passions that lead her to actions which in turn bring forward Glinda’s accusing line. This is high-level employment of leitmotiv links.

Track 6: “Dancing Through Life”

A clear structure makes this number an excellent “musical scene” in the Wicked score. (For a good definition of “musical scene,” see Lehman Engel, Words with Music) We learn about the character of Fiyero, we see Galinda flirt and manipulate, we hear Nessa’s need for love, and we witness Elphaba begin to soften towards Galinda. The appearance of musical material from “Loathing” at the exact moment Elphaba is about to extend an olive branch to Galinda (4:58) means the two women are not yet beyond their initial antipathy. Elphaba is ahead of Galinda at this point, which only makes the rift more poignant.

In the A-section, we hear another use of non-diatonic writing to color lyrics. As in “The Wizard and I,” a character contrasts two ideas through half-step melody alternations. When Fiyero questions the importance of thinking too hard and advises a soothing escape, he centers his thoughts on Ab’s. When A-natural returns on “no need to tough it,” we feel his sunny (if shallow) optimism. It seems inevitable that ostracized Elphaba will have an ill-fated connection with this ostrich who buries his head in the Ozdust to avoid life.

After a dialog break to set up the B-section (1:58), a switch to C minor supports Fiyero’s darker description of all-night reveling (2:06). Although it is hard to understand two performance decisions—the melody is changed from the published score at “meet there later tonight” (“there” being dropped lower) and the next lyric is changed from “we can dance till it’s light” to “we can dance till it lights”—this section is very rich melodically and harmonically. The non-diatonic B-naturals and F#’s add jauntiness to the dark undertone of debauchery. After the Fm chord supporting “meet there later tonight,” we get the “cleanse-your-palette” chord of Eb/Ab, to clear our ears for more non-diatonic writing. The next chord, Eb/F, can then be seen as an extended F dominant chord, functioning as a secondary dominant for the Bb7 of “We can dance till it’s light.” But, of course, this Bb7 is itself a secondary dominant, being V of iii, or Eb—the relative major to C minor where we end up temporarily set to “find the prettiest girl.” In its very harmony and harmonic rhythm, this section captures the frenetic pace of partying until dawn. The Dm7b5 chord under “give her a whirl” is the start of a traditional ii-V-i cadence to return us to C minor, but it also functions as Bb9/D, which echoes the Flat7-instead-of-IV move that is used in pop, rock, and throughout the scores of Andrew Lloyd Webber (the cadence vii-V-I). We then begin the second “half” of this section—a six-measure answer to the initial eight-measure statement.

This six-measure section includes one of the score’s best examples of harmonic dynamism. Although obscured by the orchestration, the harmonic setting of “Come on follow me, you’ll be happy to be there…” (2:27) propels the drama of “Dancing Through Life” to its climax. The first measure of this four-bar setting introduces a Bbm9 chord. This can be seen as the 7th of C minor, but it is perhaps better described as the minor subdominant of the upcoming return to F major. The quarter-note rest just ahead of “come on follow me” allows the ear to accommodate the new harmonic color of the minor subdominant before the lyrics begin. (By contrast, the analog lyrics six measures earlier are preceded by only an eighth-note rest.) The third measure of the four-bar setting uses an enharmonic shift in the melody from Ab to G# and harmonizes it with an E major chord. The absence of any change in melody note (except for how it’s written) means our ear accepts the tritone movement of the bass from Bb to E. The E major chord is functionally a C7(#5)/E, which is an inversion of the dominant of the target key of F. After a brief passing Eb7sus chord, we arrive at C7, along with a half-step move in the melody. This harmonic dynamism propels us to a re-statement of the A-section in the original key of F. The whole ride is exciting.

Track 7: “Popular”

Communicating simple charm through a complex structure, “Popular” sounds spontaneous because of very carefully crafted lyrics and music. In the shorthand of song sections and phrase lengths, “Popular” looks like this: verse-intro (6+4+4+2), A (8+4), A2 (8+4), B1 (4+4+1), A3 (8+4), transition (8), B2 (6+2, 6+2), A4 (8+4), 2nd of A (8), transition (8), end. A few measures are added in between to cover dialog moments. Musically, a crucial element is the variations in the 4-bar phrases that end each A-section. They are at the heart of this song’s charm and each involves satisfying variations in melody and harmony. They are textbook examples of how to convey ideas and emotions with music and words. In the B1 section (1:35-1:46) we are again treated to non-diatonic melody writing to express contrast. In this case, Galinda’s frank analysis (Ab’s) is contrasted with the blissful world of popularity (A-naturals).

Wicked’s balancing of breaks with links continues here. Phrase endings and beginnings are linked by clever lead-ins to the title word. “Popular” is embedded like a gemstone in many different settings: “really counts to be / popular”, “not when it comes to / popular,” “don’t make me laugh, they were / popular.”

A good performance decision led Kristin to give a powerful interpretation of “I know about popular” (1:48). The kewpie-doll voice falls away and we get a matter-of-fact, almost regretful delivery of this line. Galinda is clearly aware of the power and price of popularity. No less than the Wicked Witch of the West, the Blonde One is a product of group-think. In an arresting moment, Chenoweth and Schwartz dramatize this theme.

After the final dialog break of the song (2:52), the unappreciative Elphaba leaves her make-over mentor. Galinda is hurt, but the perky witch recovers her spirit during a colla voce break (3:07) which blends into her rousing, climactic self-affirmation.

Track 8: “I’m Not That Girl”

Well-placed 6/4 measures give breath to Elphaba and allow her to process her complex feelings. Both “hearts leap in a giddy whirl; he could be that boy” and, later, “don’t remember that rush of joy; he could be that boy” benefit from the added beats of 6/4 (0:34, 0:59). In our meeting, Stephen Schwartz sat at the piano and played through these sections in strict 4/4 time. This robbed the song of its poignancy. Schwartz’s natural instincts resulted in the 6/4 measures and they are dramatically satisfying.

In this loveliest song of the score, Elphaba realizes not only that she is not the girl Fiyero wants, but that she was not the girl her parents wanted. She is not only green with envy, she is green—and she suffers on both counts.

Although this is the only song in the score that remains in one key, the feat is accomplished by a heavy use of accidentals throughout the B-section. As Bizet did in Carmen, Schwartz captures the colors of human emotion by switching tonalities at will. Both scores use non-diatonic writing to drive home their plot points; consequently, both are rather unhinged when it comes to sustained tonality, and that freedom makes for great drama.

A subtle musical shoehorn sets up the 6/8 meter of the B-section: the lead-in to that section has quarter-note triplets in the orchestra (1:12). Another rhythmic pattern that propels the song forward is the anticipatory “push” of the accompaniment. This anticipation makes a dramatic contrast to the lyric material which looks back to disappointing moments in Elphaba’s life. There is no verse-intro in this song because the emotions here are too raw. “I’m Not That Girl” is poignant, sad, grasping, and full of resignation. If “Popular” communicates simple charm through a complex song structure, “I’m Not That Girl” expresses complicated emotions through a simpler, more direct song.

Elphaba’s last three phrases express well her emotional state, and Idina’s performance is very strong (2:30): “There’s a girl I know” captures all the complexity of Elphaba’s new affection for Glinda; “He loves her so—” has a quick finishing of “so” to mark Elphaba’s final resignation to a loveless life; and “I am not that girl” is completed by Schwartz’s fine decision to end the song on an inversion of the dominant. That ambiguous ending and Idina’s rich low note tell us Elphaba is full of potential and determination. As the evening unfolds, we will not be able to take our eyes off this fascinating character. We embraced her dream during “The Wizard and I,” and now we ache for her loneliness.

Track 9: “One Short Day”

To capture the unintentional evil of group-think, Schwartz ties into a rich Irish folk musical tradition. He gives us simple ebullient music for the moment when all Ozians—Glinda and Elphaba included—are off to see the Wizard. The happy tune indicates Ozians have no deep thoughts, but do have deep feelings. The citizens are oblivious to their leader’s duplicity, his misleading charm, and his second-banana status to his supposed underling—Press Secretary Morrible. I will leave it to the reader to decide whether this situation reminds them of a recent presidential election.

“One Short Day” is a testament to the multi-level potential of musical theater; besides its political aspect, it establishes Glinda’s and Elphaba’s new status as best friends. We arrive at this plot point, not surprisingly, by way of another break (2:37-2:50). Throughout “One Short Day” we hear melodic invention following the requirements of speech. The result is a combination of happy villagers dancing and lead characters expressing their unique personalities through recitative moments.

Eden Espinosa defying gravity in Wicked the Musical

Track 11: “Defying Gravity”

In the introduction to this song, Glinda makes an important dramatic quotation from “The Wizard and I” when she sings, “You can still be with the Wizard” (0:43). Schwartz sets these lyrics to the same melody that open the A-section of “The Wizard and I.” Glinda is trying to convince Elphaba that she can still have that earlier stage of her dream—a stage that was safe and more in line with Glinda’s conventional, conformist nature. Schwartz mines the emotion and music from “The Wizard and I” to express Glinda’s doomed hope of keeping Elphaba happy with half a dream. This is a compelling musical link.

William David Brohn’s orchestration is key to delivering the drama of Wicked. Perhaps nowhere is this clearer than when tremolos underscore the first of Elphaba’s two great transcendent moments (1:16). The violins and violas tremble and we are in a slightly non-metered universe with no clear beats. This allows Elphaba to cast aside normal guideposts and cross the Rubicon. After this point of no return, we will never again see Elphaba the same way. She will fly away from her old self and confirm the fears of those who never gave her the benefit of any doubt about her intrinsic wickedness.

One of the many powerful breaks in the score takes place as we again hear a descending figure in the bass clarinet to introduce an important moment—in this case, it’s Elphaba’s temporary seduction of Glinda to come with her (2:52-2:57). (Earlier, the bass clarinet introduced Elphaba’s “couldn’t happen here” moment in “Something Bad.”)

Another magical section begins when the two women sing about defying gravity together. This moment of unalloyed joy is as close as Glinda gets to letting go completely of the need to act all the time (3:23). For once, Glinda is unselfconscious. For a few moments, she is not defined by her high-maintenance persona and she joins Elphaba in forging a path independent of social status. They are both through playing by other people’s rules.

Despite this liberating flight of fancy, Glinda remains fearful of change, so Elphaba must issue her plaintive, “Well, are you coming?” (3:45). This is one of my favorite moments on the CD; the performance decision that led to Idina’s line reading was ideal. The line is full of the last moment of hope and the first moment of bitter resentment. Elphaba subsequently feels abandoned and angry. Despite this powerful separation, Glinda and Elphaba sing the “Unlimited Theme” together: both are hoping the best for each other, fully aware of their permanent estrangement and the pain it will bring. We are then given complete silence for a moment before hearing both Elphaba and Glinda sing “my friend” (4:20). We thus get a taste of “For Good.” We must wait a long time before we again see Glinda and Elphie so close.

The beginning of a dramatic build (4:23) opens arguably the most exciting 1.5 minutes of the score. You should have goose bumps as the French horn soars and looking to the western sky, we see Elphaba blazing (4:37). This moment is made arresting by Idina’s contribution of putting “so if you care to find me….” in the stratosphere of her belt. After a brief, dramatic slowing of the beat, we are dropped into some churning, charging orchestration as Elphaba flies solo (4:46). If your pulse is not raised by this point, check your arm for circuitry. Elphaba declares her independence and embraces—with the right shading of doubt—her future of solo flight. This witchy Lindbergh is electric, and Schwartz delayed the point at which Idina gives us long belting passages.

As the song reaches its climax, strategic changes in tempo again highlight important moments. After the re-entry of the chorus completes the dramatic structure of Act I, Elphaba, Glinda, and Ozians clash powerfully (5:29). At the peak, while Elphaba holds her note defiantly, we hear Glinda sing—as she did at the start of the song—”I hope you’re happy.” This time, however, the lyric phrase is set on top of the musical material we heard at the very beginning of the show—the “Wicked Witch Theme.” And the deletion of the word “now” from Glinda’s line suggests that despite Elphaba’s decision to defy authority, Glinda hopes Elphie is happy in the end.

We also recommend Chapter 20, “Somewhere Over the Keyboard” in Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to Wicked by Carol de Giere. This chapter includes quotations from Schwartz about the Wicked score.

Robert Vieira is a musical dramatist whose music and words can be found on over 50 video games, TV’s Sesame Street, interactive toys, and a history dissertation at U.C. Berkeley. See IMDB link here. Hyperlinks © Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary

Trackbacks/Pingbacks