I am a huge fan of Sammi Cannold’s work and really enjoyed a presentation she offered a few months ago for Maestra Music. Sammi has a really good handle on the relationship between directors and writers. She has worked with many new works including How to Dance in Ohio, opening on Broadway this fall at the Belasco Theater. Sammi is a theater, film and television director who is one of Forbes Magazine’s 30 under 30 in Hollywood Entertainment. She was recently honored as one of Variety’s 10 Broadway Stars to Watch for 2023.

Below are some highlights from a masterclass she did recently for our MusicalWriters Academy community. Her insights are too good not to share!

The Writer-Director Relationship

Sammi: I am really excited to be talking about the writer-director relationship because I think that so often in theater, we know our lane, we know what we do, we think we know what our collaborators do. I have found through conversations over the years with collaborators in the other jobs, that I don’t actually really understand what they do or the ins and outs of what’s difficult about their jobs, or what’s difficult about their relationships with other positions in theater. I think it’s really healthy for us to be talking across positions to say, “here’s what it’s like from my perspective” and “I’d be really excited to hear what it’s like from your perspective.”

Everything I say today will be coming from my perspective as somebody who is, as far as theater is concerned, only a director. My opinion and my experience of relationships with writers is very much specific to the experiences that I’ve had. It is just one director’s opinion on how these relationships can work. I’ve been very fortunate to have a lot of relationships with writers, some very successful and wonderful and fruitful and happy, and some less so. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what puts a relationship on one end of that spectrum or another and why. I’m going to share today my point of view on how to navigate in the happiest, best possible way. Remember, these are just my opinions and there is no “right answer”.

We’re going to cover the process of identifying a collaborator, in this case, a director, the process of initiating that collaboration with that director, the process of onboarding that director, and the feedback and notes process. We will then discuss what the director is going through on a daily basis as they’re trying to understand what you’re going through on a daily basis. We’ll also talk about the preview process, and what to do when a collaboration isn’t working.

Identifying a Collaborator

Sammi: So, identifying a collaborator. I’m taking this from the perspective of you have a new musical, you have an idea for a new musical, you’re writing a new musical, and you need a director. When you’re thinking about who that director should be, there are a number of things that I would suggest are really important in the qualifications for that particular person.

The first is experience with or proclivity towards musicals. As directors, when we go to see musicals that are directed by directors of plays moving into musicals for the first time, you can often tell if people have trained in directing musicals, or if they’re coming solely from a background of directing plays, which is not at all a dig at people who direct plays. Directors of plays are so brilliant, but it is a very different skill set in my mind. Having an understanding of music, having an understanding of how a musical flows, having an understanding of the size and scope of many musicals is a very different beast than someone who is directing a two hander at a kitchen table. If somebody asked me to direct a two person play at a kitchen table, I know that 95% of the time I’m the wrong director for that play. My skill set is more in large musicals and moving pieces versus the ability to really dissect text and intimate scenes. The ability to navigate 20 pages of text in one location is such an intricate skill set that those of us who do the big physical musicals don’t necessarily have, and vice versa.

Second, prior work that suggests a matched skill set is also important. For example, if your musical is very historical in nature, someone who’s directed a lot of historical musicals might be a really good fit for that. Look at a prior body of work and say, what suggests to me that they would be right from my show?

Third is readiness for a given opportunity. This one is really sort of elusive because how we measure where we are in our careers in this industry is kind of all over the place. But I think that you want a certain degree of assurance that the person that you’re hiring is going to be able to handle what you’re putting in front of them. Now, that doesn’t mean that if you are writing a musical that’s going to be performed on Broadway, that you need somebody who’s directed a musical on Broadway before, because everybody has to have their first at a certain level. For example, if you anticipate that this is going to be a musical with 30 people you don’t want to hire somebody who’s only ever done something with two people in it. Obviously, as somebody who is young, I’m a huge believer in giving people chances, I’m the beneficiary of people giving me a chance before I was at a certain level. You need to have something that demonstrates that the person you’re asking to do what you’re asking them to do can really handle it.

The next is about process style. Different directors have different styles of process. For example, I’m very prep oriented in my process. I plan everything out ahead of time and I come into the room with a plan. I’m very specific about it. Sometimes I find that doesn’t match with what a writing team wants in a given case. It’s really important when you’re considering collaborating with someone to ask them what is their process and make sure it gels with what you want.

Identity is also really important, because there’s so many conversations around this happening right now. What are the points of view that you currently have on your team? Is there a point of view that’s missing? Can you, in looking for a director, bring that point of view into your world? Is your piece about a certain group of individuals that you don’t currently have represented on your team? For example, I get asked to direct musicals, about women, written by men. I appreciate that the male writers are bringing a female voice into the conversation and hope that by combining our identities we can have different points of view at the table.

The next is reputation and references. It is important to find out about how a director functions and if you’re going to enjoy working with them by talking to people who already have. I do this every single time I hire an actor for something more than a week or two. If I were somebody who hired directors, I would want to do the same to understand what past experiences with this person have been like to confirm it is going to be a healthy, wonderful collaboration.

And a last quick thought – do you want them to be more than a director? There’s a very fine line between director and dramaturg, and most directors assume they’re going to be doing a lot of dramaturgy anyway. Do you want a director choreographer on a given piece? Do you want a director who’s involved in design as more than just a director? We will discuss more about this later!

When is the right time to reach out to a director?

Sammi: When is the right time to reach out? Is it before you start writing? Is it once you have a first draft, or is it once you have an upcoming opportunity with actors?

My suggestion would be that the right time to reach out is when you need a director for something specific. I’ve often come on board and then do nothing for six months because they’re still working on the first draft. Bringing them on at a time where you’re about to hit a certain milestone feels really important.

For example, if you have a first draft and you really want the director to weigh in on this draft before you move forward, that’s a great reason to start bringing on a director. Or if you have been offered the opportunity to do a reading of your show and, you need someone to direct it, that’s a great time to bring on a director. In my mind, the only reason to bring on a director before you start writing is if, the piece that you are envisioning is very physical or conceptual in nature, because then the director can help craft the visual world of the show from step one. If I’m approached with, “I’m thinking of writing a musical about this, do you want to come on board?” – my personal response is, “I don’t know if I’m the right director for it until it exists.” I really believe so strongly in directors and pieces matching each other. And if a piece doesn’t exist, how can a director know? And how could a writing team know if the two are a fit?

How does a writer reach out to a director?

Sammi: My feeling here is that anything goes: email, social media, in person, via reps, any of the above, feel appropriate to me. It’s on directors to make themselves reachable and to have their information on the internet. I don’t think there should be any sort of hesitation in the means of going about doing it. Yesterday, this has never happened to me before, I got a call from a cell phone number I didn’t know and it was someone I didn’t know asking about a musical.

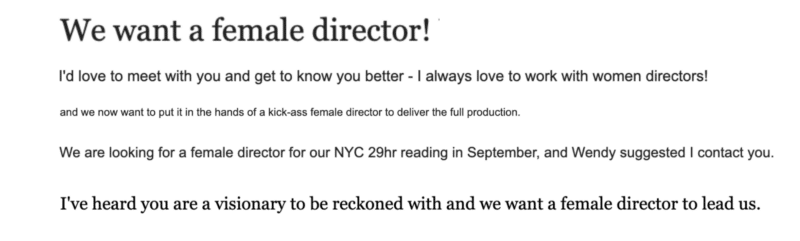

What to say and what not to say is really a subjective thing, but I will give you the point of view of being a young female director. I often get emails that look like this:

I share it with you, not as necessarily a critical thing, but more as a thought-provoking thing of what it means to tell people that we want them to work on our team because of their identity. If you want to hire me because I’m a young woman, I am all for it, but that doesn’t mean that that’s the only reason that you’re hiring me.

If you’re reaching out to a potential director, consider these questions: Why do you like their work? Why do you think they’re a good fit for your piece? Make that the starting point of the conversation. Otherwise, I might believe that you’re not just reaching out to me, you’re reaching out to me and a bunch of other women and hoping that one of us says yes. There’s an implication there that the work is less important than the identity which is an interesting dynamic to set up at the beginning of a collaboration.

When do you make an agreement with a director?

Sammi: When to make an agreement is something that I don’t think we talk about enough in this industry. So often, directors, particularly early career directors, will come on board and work on a show for several years without anything in writing to say that we are working on that show. That puts the director in a precarious position, because at the end of the day, the writer could say, “Thank you so much for all your notes for these past two years. I’ve actually decided I’m going to go in another direction. I appreciate all you’ve done,” and that would be that for that director.

I feel it’s really important that writers and directors, if they’re going to work that way without a producer or any sort of money or institutional support, have at least a collaborator’s agreement between the two. So that if, for whatever reason, it’s determined that there should be a parting of ways, the director hasn’t just given time freely without any sort of future attachment to the piece. It’s sometimes an uncomfortable situation to broach at the beginning, which can be made much easier by a writer saying to a director, “How do you feel about having a collaborator’s agreement up front?” Different agencies and directors have templates for this if you’ve not seen one before. A few years ago, I hadn’t seen one, and then a friend sent one to me, and I thought it was quite amazing because it provides protection for the director. You hope you’re not going to part ways, but it signals a level of respect to the director you’re bringing on board.

Next: is the director a conceiver? Hadestown was landmark in this conversation because it brought attention to the idea that a director is a conceiver. It’s important to ask that question when talking with a director.

Taking “no” as an answer is also crucial. Oftentimes directors will pass on a project, citing a lack of bandwidth or a full schedule. I’ve seen writers then try to make it work anyway. My suggestion is when a director says no, take it as no and find someone who will passionately say yes. Directing musicals is hard and time-consuming. If someone is already showing resistance, it’s not going to be productive down the line.

Collaborating with a Director: Notes and Feedback

Sammi: The feedback and notes process can be where directors and writers encounter difficulty. Notes go both ways. I appreciate when writers give notes to me on staging, design, etc. The healthiest collaborations have notes flowing both ways. It’s crucial to establish what you want and don’t want from a director at the start. I once worked with a playwright who said the play was locked and asked if I wanted to direct this version. Saying that to a director up front avoids issues later.

Establishing a clear process for feedback and notes up front is also important. How do you like to receive notes? How does your director like to receive notes? The timing of giving notes is something writers might not know about. Getting a note in the middle of a scene can be challenging, but discussing the note during a break works better for me. Talking with your director about how they process notes can provide a system. Understanding the timeline of implementation is important, too. If a writer gives a note on a costume, they may not realize that the costume shop has specific hours and they might not see that note in action until the following day.

Understanding the director’s schedule

Sammi: Understanding a director can be a bit elusive and I would really love to go to the sister talk of this about ‘understanding a writer’, because I think there are probably many, many things I don’t understand about being a writer. But the number one difficulty, I personally experience with writers, understanding directors, and I know this is a common thing from talking to fellow directors, is understanding a director’s slate and schedule. In order to make a living as a director, working in non-profits, sometimes commercial theater, you have to be directing multiple productions a year. Financially speaking, if this is your sole source of income, you have to be directing about five productions a year to live in New York City.

As a result of that, directors are very often in rehearsal from 10 to 6 (and as I’m sure you know, 10 to 6 really means 9 to 7). I find that when I’m rehearsing something else, sometimes writers will get very frustrated that they can’t reach me during the day. I try to help writers understand that when a director is in the room on your project, you want them to be fully focused and in the zone and paying attention to your project. Not getting on a Zoom about someone else’s project while the choreographer is putting up a number.

Compassion for the challenges of the job is something that I think really should go both ways, because I don’t think directors understand how vulnerable being a writer is. I don’t think they understand how hard it is to sit down and write. But on the flip side, being a director is so hard, particularly a director of musicals. Currently I’m working on four musicals right now and each of them has a company of actors between 15 people and 30 people. So you multiply that and that’s basically 100 actors give or take and then add all the designers! There is an interaction that’s expected – that a director sees and communicates, interacts with and has a relationship with every single person in that room. I see it as my job to make every single person in that room feel like I understand what they’re doing, I value what they’re doing, I’m really grateful for what they’re doing, and that I have a personal relationship with them. Having that bandwidth, and I don’t necessarily mean time-wise, but emotionally, and sociologically, is something that is very exhausting. It’s a blessing, we’re all so lucky to get to do what we do, but I really appreciate when I work with writers who understand that this navigation is tricky.

In the preview process, it’s really important to understand that a director is very often aggregating feedback. I think it’s helpful if feedback isn’t coming from many different sources, it’s coming from one. Oftentimes I’ll say to the producers and any other stakeholders in the situation, “please give all your feedback to me. I will sit down and give it to the writers.” It’s one consolidated process. I love when I work with writers who have priorities in what is most important to them. I’ve worked with writers who will say, “I know this scene is the backbone of this show. This is really important to me.” I’ll take all these notes over here, but this is really important to me. I don’t view that as stubbornness. I view that as understanding what it is you’re writing and prioritizing what is important to you.

How to know when a collaboration isn’t working

Sammi: When it comes to identifying when a collaboration isn’t working, there are a few telltale signs. One of the most common indicators is a lack of engagement from the director. If they’re not responsive, if they’re not actively reading the drafts you’re sending over, or if they’re not game to hop on a call and discuss things, it might be a sign that they’re not as invested as you’d hope.

The second is artistic differences, which is obviously a bit self explanatory, but if you’re just not seeing eye to eye, that may ultimately mean that the collaboration isn’t the right collaboration. It may be fixable, but it may mean it’s not the right one.

Then there are process issues, which many of us have probably encountered in one form or another. If there are consistent hiccups or disagreements about how the work should be approached or executed, it’s worth taking a step back and evaluating the collaboration.

It’s essential to trust your gut feelings. The initial stages of a project, leading up to the production, are generally less intense than the production itself. If you’re sensing issues during these preliminary stages, it’s a good idea to address them head-on. The pressure and intensity will only ramp up as you move closer to production.

However, communication is key. Before making any drastic decisions, like ending the collaboration, it’s crucial to sit down and have an open conversation about any concerns. The director might not even be aware of the issues, and discussing them can lead to a resolution. It’s always better to address concerns directly and give the collaboration a chance to mend before deciding to part ways.

Questions from Writers

Would you expect, at minimum, for a director to read some or all of a show before deciding if it’s a fit? Does it depend on the project?

Sammi: I think that a director could say NO from reading some, but they couldn’t say YES from reading some. They would have to read it all to say yes. Unless all doesn’t exist yet. Right? If you’re saying, “okay, we want to bring a director on board, but we’ve only written Act One” then they could potentially choose to come on board then. I’ve never been in a situation, nor heard of a situation, where the whole show exists and a director reads ten pages and says, “yeah, I’m in.” They would want to read the whole thing.

Circling back to the director as a conceiver, I assume that that means a different kind of agreement. Any advice on what that looks like?

Sammi: That’s a really great question. I just had an agreement like that, and I saw in the chat, Ed was saying the Dramatists Guild has model agreements. There is language floating around between agencies and directors. It basically memorializes the idea that you are more than a director and at such a point as profit participation comes into the conversation, the contract will reflect that.

How much should a writer expect to pay a director?

Sammi: I believe strongly in sharing this kind of information because there’s no central place you can go for information about how things work in our industry. I ask my friends all the time “how much did you get paid for this because I don’t know how much I should get paid for this.” To some extent, agents, if they’re in the picture of a negotiation, can help to provide references. SDC, the directors union, does have a standard rate that you can go above, but you can’t go below for directors who are in the union. For directors who aren’t in the union, they can be paid whatever you or the producer want to pay them. The thing that’s deceptive about 29-hour readings and directors is that you may think, “oh, it’s only a week of work, they should be paid what someone would need to be paid for a week of work.” But the reality is that directing a 29-hour is really about three weeks of work. Casting, particularly for a musical, is many hours, especially if there’s not a casting director. The lower end of what professional full-time directors who are unionized would get paid for a reading is about $2500.

What factors are important to you in selecting a show? How do you rank concept, creators, stage of development, funding, goals for the show or other attachments?

Sammi: I’ve heard the system before that you have to have the Three P’s: pay, people, and the piece. And you need to have two out of the three P’s for it to be something that you should do. So either the pay and the piece need to be really good, or the people and the piece need to be really good, even if the pay is not good for you to want to do it. For example, you could want to do one project because there’s someone you’ve always wanted to work with working on it, or you could want to work on another project because you just fall in love with the material. I think both happen, different combos happen to different directors all the time.

What piques your interest the most in choosing a show you want to do? Could you give some contrasting examples?

Sammi: Yeah, this one is recently on my mind. A few friends of mine wrote a screenplay and there’s no money attached to it. There’s no concrete opportunity attached to it. I’ve not read any screenplay I’ve loved this much in ages. And I said, let’s do this. Let’s figure it out together. Even though there’s no money, there’s no opportunity. That’s an example of people and piece outweighing the fact that there are zero dollars attached to it. Hopefully one day there will be, but right now, there’s zero.

I think directors are often really attracted to projects with opportunities already being lined up. Oftentimes writers with new pieces will come to a director to help them find an opportunity. This is not a bad thing at all. It makes a lot of sense. Directors have a lot of relationships with institutions and with producers. It’s totally logical, but it does constitute an extra level of work for that director before there’s anything contractual on the table. A director has to really have the bandwidth to say, “okay, I can do that.” Sometimes you’ll get directors who will say, “I really love the piece, but can we revisit this once there’s an opportunity on the table because I don’t currently have the bandwidth to bring it to XYZ theaters.” Or “I have another project that I’m responsible for getting a home right now and I don’t want to dilute my ability to get that project a home.” That’s no offense to your piece. It’s just the reality of how you navigate being a freelance director.

What percentage of writers are reaching out to you versus producers? Do you see a trend at different stages? Have you reached a level where you are only interested in a project if producers/investors are involved?

Sammi: I would say it’s about 50/50. For me, I read and think about everything. Just because sometimes a project that has producers and a ton of money behind it could not be very good. It could have landed there because of various different factors. I mean, “good” is subjective, but from my opinion, not very good. Sometimes an amazing piece could be from a first time writer. I have the privilege of getting to see all those things and say, “I really respond to this one” or “I don’t respond to this one” and I’m not going to be that discerning about where things are coming from. That said, is it more work to come aboard something that doesn’t have infrastructure around it? Absolutely.

As an SDC director – for a small show at the staged reading/workshop level, would you be able to waive the right of first refusal? At what point would you need right of first refusal?

Sammi: This is something that, for better or worse, is pretty hierarchical in this industry. Most directors working on Broadway, and I hate to be like that about it, but their agents won’t let them do anything without right of first refusal. Anything. It doesn’t matter what it is. This doesn’t mean that you can’t later buy out a director if you don’t want to work with them. I see that happen a lot, but nobody working at the Broadway level will do anything without right of first refusal unless they have bad agents. I also think of it as a vote of confidence from the writers that I’m working with – it’s saying “we’re really in this to win it together” and I appreciate that.

Can you compare directing a first time production versus directing in a workshop? What are your rules for a workshop?

Sammi: This is an interesting concept. We were talking about working with somebody who says, “hey, this script is frozen” and that is something that is a little bit different in our situation working on new works. When you’re working at regional theaters on licensed work, all of that work is frozen. You don’t get to change a song or cut a character. So, this is an interesting comparison to make between working on new workshop developments and working on existing works. When you work on a revival, like West Side Story, you accept that the text is the text and you’re going to play within that playground. I find that to be fun and oftentimes freeing because my brain isn’t simultaneously thinking, “is the scene right? And is my staging right?” which is what I have to do on a new musical. I’m just thinking, “is my staging right?” Because whether or not the scene is right doesn’t matter. It is what it is. And, hopefully if you’re directing good revivals, the scene is great.

Working on a new musical, you have to have more antennae. That’s why it’s good to have somebody on your new musical who has worked on something new before. If you are hiring a director for a new musical and they’ve never worked on a new musical before, maybe it’s good to hire someone who has worked on a new play or somebody who has assisted on a new musical, so that at least they have the muscle of how to make changes quickly and how to implement changes in the room. That’s something that’s very idiosyncratic. I was a production assistant, an assistant director, and an associate director on new musicals before I even touched being a director of new musicals. Understanding how the system works was really key to my being able to run the room in those environments.

Can you tell us a little bit about your journey with How to Dance in Ohio and when you came on board?

Sammi: I came on board in early 2020 right before the pandemic. The show was originally directed by Hal Prince and it was the last thing he was working on. When he passed, they sadly needed a new director. I ended up on the show because I followed Jacob, the composer on Instagram, and he followed me back then he DM’d me: “You know, I saw your production of Evita. Do you want to get coffee?” We got coffee. The show is about seven autistic young adults and my brother is autistic. Autism advocacy is something that I’ve been pretty immersed in. We started talking about it and that’s sort of how the journey started, which people are like, “That’s crazy. Your Broadway debut came out of an Instagram DM.” These things come from anywhere and since then we’ve done a reading, two workshops, a production out of town, and then now we’ll do the Broadway production in the fall.