This post is the second (Part II) in a series called Orchestrating a New Musical, where we’ll be covering these topics:

- Part I: Setup and Instrumentation

- Part II: The Rhythm Section

- Part III: The Wind Section

- Part IV: The String Section

- Part V: Other Instruments

- Part VI: Putting It All Together

- Part VII: Logistics

Today’s entry will be a discussion of the Rhythm Section of the orchestra, and what to do with this versatile group of musicians.

What Is The Rhythm Section?

Let’s begin by defining what a rhythm section is. The rhythm section of a musical theater orchestra is usually defined as the keyboards, guitars, drum kit, and bass. This section is so named due to its obligation to keep the rhythm and groove throughout numbers. The drums and the bass should lock in during upbeat numbers, keeping the energy up and the excitement present. The keys and guitars help provide interest and necessary color, cueing the listener in to what style we’re listening to.

The drums and the bass should lock in during upbeat numbers, keeping the energy up and the excitement present. The keys and guitars help provide interest and necessary color, cueing the listener in to what style we’re listening to.

Note that I generally separate auxiliary percussion from the rhythm section, even though some aux percussion instruments can be used to construct groove (shakers, congas, etc.). We’ll cover aux percussion in more detail in Part V.

We’ll begin by examining each instrument individually, then touch upon groove construction before finishing with this section’s listening guide.

The Bass

The bass is the rock of the orchestra. In fact, before we continue, I must emphasize this point: the bass is the rock of the orchestra. There is a disturbing trend of placing critical bass parts in the left hand of the keyboard, in order to conserve resources, but fight this tendency! The bass is necessary for so many styles of music integral to the theater. In jazz shows, the physical vibration of the air from a double-bass is critical to the integrity of the sound, and in contemporary musicals, the feel of an electric bassist is the lynchpin to authentic pop and rock groove.

There are two main categories of basses: acoustic basses, which you’ve probably seen in symphonies and with a jazz big band, and electric basses, far more common in rock bands and contemporary styles of music. Within these categories, there are the typical four-string basses, which can reach down to a low E below the bass staff, and five-string basses, which reach down to a low C below the bass staff. Some basses have extensions on that fifth string to go down to a low B, and a select few even have more strings, but it’s safe to expect that a low C is the reasonable limit. If you can, I recommend keeping the part above the low E, which would enable a greater breadth of players to play the part than just those who own five-string basses. This can be particularly important for amateur or educational orchestras, where players may be lacking the proper gear.

The two types of basses (acoustic and electric) are right for some styles and wrong for others. For example, I would never write for an acoustic bass in a rock song. For this reason, I often ask my players to double on both acoustic and electric in order to accurately perform different styles.

The Drum Kit

Next, let’s take a look at the drum kit. A versatile and sprawling instrument, the drum kit is comprised of several individual instruments. Most drummers will customize their kits, but the following instruments are safe to expect any drummer to have:

- Bass (Kick) Drum

- Snare Drum

- Floor Tom

- Hi-Hat

- Crash Cymbal

- Ride Cymbal

The pieces above represent the core of the kit, but other peripherals are often available, and you should feel comfortable calling for them:

- High and Low Toms

- China Cymbal

- Triangle

- Wood Blocks

- Shaker

These peripheral instruments are also commonly found in the percussionist’s array of instruments, so depending on your instrumentation and setup, it may not be necessary for the drum kit player to handle these auxiliary pieces.

The drum kit, along with the bass, provides the foundation of the groove. Drum kit writing is incredibly unique and a challenge for non-drummers to write out, but creating a specific groove is super important to evoking style. The drummer provides the tempo and keeps everyone locked in, so I always spend extra time crafting the drum part. If you’re not familiar with drum writing, I’ve provided an example below in the “Constructing a Groove” section. I also highly recommend asking for feedback from the drummer on their part. I have grown considerably as an orchestrator by soliciting feedback from instrumentalists about parts, in particular the rhythm section, where writing is so idiomatic.

Guitars

Let’s talk about the guitars next. There are two main categories of guitar, just like the bass: acoustic and electric. The acoustic guitar is often found in, well, acoustic styles: country, folk, early jazz, singer-songwriter. The electric guitar is often found in more contemporary styles: rock, pop, R&B, gospel, soul, funk, bebop. There’s also a third category, the semi-hollow bodied guitar, that is usually found in medium swing jazz bands and big bands.

I often expect my guitarists to pack multiple guitars to the pit in order to get the sound I want for each number. Oftentimes I want the ballads to be peppered with the simplicity and beauty of an acoustic guitar, while the big showstoppers contain the driving energy of the electric. Specialized instruments are also occasionally called for, such as the mandolin or banjo.

The electric guitar also has several peripherals that could take up an entire article one day, but I will quickly cover one category here: pedals. Guitar pedals are some of the most fascinating devices I have ever seen. They (along with the amp) alter the tone of the guitar and create special effects that are essential to so many styles. The “wah” pedal is used to create the characteristic “wah” sound in funk, the chorus pedal is used to create the brighter sound typical in pop, and the overdrive and distortion pedals are used to create the crunch and grit of rock and metal. Needless to say, learning the intricacies of guitar pedals is a surefire way to get your guitarist on your side, and a great way to evoke certain musical flavors for the listener. I won’t spell out specific use-cases here for the sake of space, but perusing full scores or talking to a guitarist will quickly get you up to snuff. Even after many years of orchestrating, I will still frequently work with a guitarist in early rehearsals to lock in the exact pedals I want for each passage in the score, as the pedal choices color the score so strongly.

Keys

On to the final member of the rhythm section: the keys. Keys encompasses two main instruments: keyboard and pianos. Keyboards are the predominant instrument by a long shot due to their versatility, though acoustic pianos are not unheard of, especially in shows emphasizing acoustic scores.

Pianos, when they are used, are nearly always upright due to space, but nonetheless when an authentic and classic sound is desired, you cannot beat a real piano. Keyboards, on the other hand, are electronic and can provide a range of sounds that are unprocurable in any other way. Connected to a computer, keyboards can be fed data and change patches at a moment’s notice, enabling a keyboardist to play a harmonica sound in one beat and a string sound in the next. This sort of versatility and agility is incredibly powerful, and has led to the mass migration of piano parts over to keyboards.

While keyboards are tempting for so many reasons, I always take a moment to ask myself why I’m not just writing a piano part instead. An acoustic piano will always sound better than a MIDI piano when the two are playing a piano part, so unless I will be taking full advantage of the keyboard’s versatility, I default to a piano. That said, after instrumentation considerations are evaluated, a keyboard is usually the way to go, especially in smaller pits. With only five instrumentalists, having that keyboard can be crucial to filling in the sounds of an otherwise large band, adding string strength, brass, and sounds only possible from a synthesizer.

Constructing A Groove

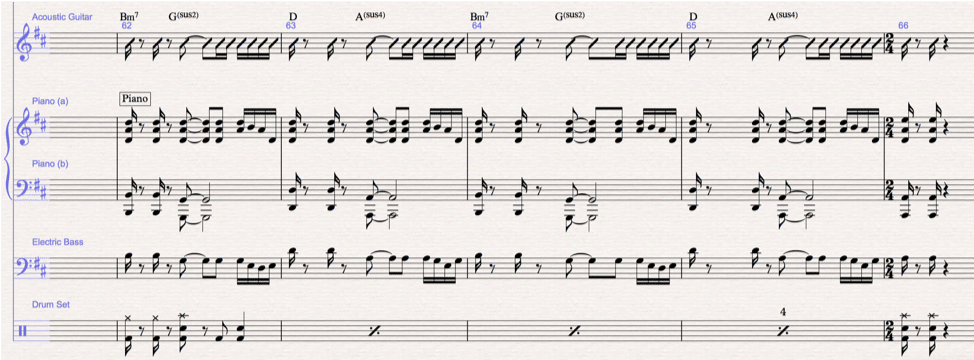

Let’s take a look at an actual groove I created when orchestrating. Below is “A Different Road” from Mirror, Mirror.

“A Different Road” from Mirror, Mirror, Music and Orchestration by Travis Frank, Lyrics by Travis Frank and Megan Ruppel

This is the chorus of the song, so this is the groove that locks in the feel of the song. For reference, this piece is at about 106 BPM, and we’re going for a solid pop groove. Let’s begin with the bass, since so often this sets the feel for everyone else. We can see that I chose to make the first two beats quick, followed by a held note and then a riff. This is a very busy bass part, and it works because the melody is a sustained whole note. When the melody gets out of the way like this, the rhythm can be busier and more complex. This contrast allows the different parts of the song (melody, harmony, and rhythm) to shine at their own moments. The drums are mostly in line with the bass, omitting a fill in favor of a simple snare backbeat on beat four.

The piano and the guitar follow the bass pattern nearly identically, with the guitar receiving an extra sixteenth note upbeat on beat three, something a little more characteristic of the instrument. Combined together, the four instruments have the first three hits together, with the second half of the bar diverging just a little to allow for more appropriate maneuvering for each instrument. This creates a cohesive and solid groove for the rhythm section to lock in on.

This is only one way to approach creating a groove for the rhythm section, and it’s not always correct to have everyone be playing the same hits. Sometimes you just want the piano pounding out those hits while the guitar, bass, and drums provide rock-solid quarter notes and pickups. Style and melody should always dictate what approach you take.

Other Uses For The Rhythm Section

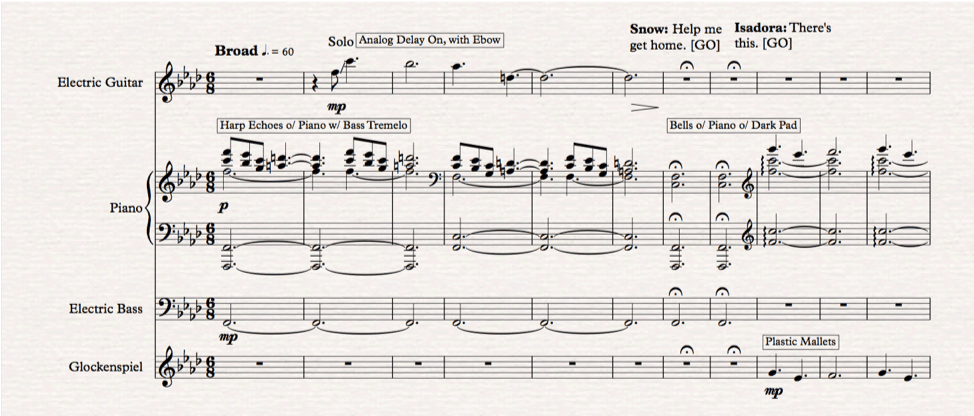

Amidst all this discussion of groove and rhythm, it’s easy to forget that the instruments in the rhythm section can play melodic and non-rhythmic parts just as well as any other instruments, and bringing them in in this capacity can provide some much needed color. Below is “Be Brave Reprise” from Mirror, Mirror.

“Be Brave Reprise” from Mirror, Mirror, Music and Orchestrations by Travis Frank, Lyrics by Travis Frank and Megan Ruppel

As you can see in this example, I chose to give the keyboard, electric guitar, and drum kit (on glockenspiel, an auxiliary instrument) some welcome melody and solos. Especially with the Ebow on the electric guitar (another peripheral), there are some wonderful new sounds that the listener is not used to hearing. Try to find places in the score where the rhythm section gets a chance to rest and play some melodic lines. They’ll thank you later, and the variety it brings your score is invaluable, especially with smaller pits.

Rhythm Section Listening Guide

The listening guide is comprised of two parts: the first to review concepts covered in this post, and the second to preview themes we will be covering in the next article in this series.

Part I – Rhythm Section Review

“I Am The One” – Next to Normal (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

Orchestrations by Michael Starobin and Tom Kitt – Music by Tom Kitt, Lyrics by Brian Yorkey

- What instrument is driving the groove during the verses? How do the other instruments support this instrument?

- Listen closely to the bass part. How does it change between the verses and choruses?

“Real Big News” – Parade (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

Orchestrations by Don Sebesky – Music & Lyrics by Jason Robert Brown

- How complex is the drum part? Why? Who is providing the complexity in the groove?

- Is the bass acoustic or electric? Which is more appropriate?

Part II – Wind Section Preview

“In My Own Little Corner” – Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella (2013)

Orchestrations by Danny Troob – Music by Richard Rodgers, Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II

- What wind instrument is bulking up the background pads? Which are filling in around the melody?

- When the melody is doubled in the winds, which instrument does so?

“Road to Hell (Reprise)” – Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording)

Orchestrations by Michael Chorney and Todd Sickafoose – Music & Lyrics by Anaïs Mitchell

- ~2:40 – What is this instrument? What effect does the fill have on the listener?

- Does this instrument ever join the groove of the song? Why?

Love this! Now when’s the wind section part coming out? (I hope you’ll also get to cover brass in that segment, because not too many people these days write much brass parts in new musicals.)