Mastering College Musical Theatre Auditions: Sound Advice for the Student, Teacher, and Parent by David Sisco and Laura Josepher

There has been marked change in the genre of musical theatre given its relatively short arc, from Oklahoma to Hamilton. Even in the midst of this change, we have enough perspective to see the sometimes jolting evolution of the book musical. For instance, there have been substantial changes in how a scene dovetails into a song and how writers have rethought show and song structure given the influences of other mediums, like movies and pop/rock music. Nowhere is this change more sharply seen, however, than in the demands on a musical theatre performer. As a result, many performers continually struggle balancing an active career with maintaining good vocal health. As musical theatre writers, this demands our attention.

I became interested in this topic several years ago, having personally seen more and more adventurous writing for the voice. As a private voice teacher and musical theatre writer currently associated with the BMI Advanced Musical Theatre Workshop, I’ve had the opportunity to witness all sides of this issue. I’ve also presented a session entitled “Vocal Health on Broadway and Beyond” at the national and international conferences. In it, I compared how vocal health issues are prevented and treated on Broadway, London’s West End, and in touring productions in Australia. I’ll spin out some of this information in a moment, but let me start by saying my findings were not exactly positive. There’s a lot of scary singing happening out there, and some of it is due to what I see as irresponsible vocal writing.

It is not an over-exaggeration to call this a huge issue in today’s musical theatre industry. And yet, it is one that is still relatively ignored because of the stigma attached to vocal damage. I’m grateful to MusicalWriters.com for giving me a platform to talk to writers directly so we can begin making a positive impact on this issue.

The Research

Let’s start with a little background research to underscore why considering the musical theatre performer is an important conversation.

There are a number of challenges the musical theatre performer faces in today’s industry. Most pressing are the vocal demands of a musical theatre score. Some contemporary scores require what is considered heavy vocal load singing for longer periods of time than is healthy. This creates longterm problems for the performer, which can play out long after a show has closed.

I had the opportunity to interview several established Broadway performers through an anonymous survey for my “Vocal Health on Broadway & Beyond” session. Through it, I discovered 85% of respondents said it was common for them to experience vocal fatigue after a week of shows. Of those responding, 55% percent noted the fatigue was as a result of the demands of the role and/or scheduling demands (i.e. 8 shows a week on top of other rehearsals, etc…). When asked how long the fatigue lasted, two thirds of performers said 2 or more days with more than a quarter saying the issues persisted for 5 days or longer. And, what’s more, almost a quarter of participants said they suffered temporary or sustained vocal damage because of performing in a Broadway production.

Professional Pressure

The musical theatre performer is often left to his/her own devices when in vocal trouble. One performer anonymously noted, “I was made to feel guilty if I called out and [the producers] don’t pay for the doctor or the drugs.” Workers Compensation does not cover vocal health issues. Fear and paranoia only fuel this issue.

Kevin Massey in A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder. Courtesy www.kevinmassey.com

In fact, at times, creative teams and producers can make things even more challenging for the performer. I interviewed Kevin Massey, who understudied the role of Huey Calhoun in Memphis on Broadway, and also did the touring production of A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder. He told me about a situation he was put in during a final call-back:

“For the Queen musical We Will Rock You, they flew me out to Vegas to audition, which never happens. One of the creatives said to me, ‘It sounds quite nice. It’s quite riveting, but it sounds like it needs to hurt more.’ And I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, how do I do that? Do I want to do that?’”

Audition Demands

Beyond increased vocal demands, there are also understandable concerns about the vast range of styles a musical theatre performer must now embody in order to remain competitive at auditions.

Let’s look at the breadth of musical genres in Broadway shows in the last couple years: The Band’s Visit (world music), Bright Star (bluegrass), Come from Away (folk/pop), Dear Evan Hansen (pop/rock), Hamilton (hip hop), and Spongebob SquarePants: The Broadway Musical (you name it). We could argue about these genre classifications, but we’ll let future historians do that. The point is: there are tons of different musical styles on Broadway, between new musicals and revivals.

In the past, actors may have only needed five songs in their audition book. Today? Try about twenty. But singers can’t just have twenty songs in their book. They must intimately understand the style markers of each genre within the context of their technique. To say that’s a lot of work is an understatement.

Most musical theatre performers don’t have the time or the financial resources to engage voice professionals who can help them work these different styles into their body. It is not uncommon for singers to instead delineate styles by ear, which ends up creating poor vocal habits in the long run. Roles with high vocal load demands only exacerbate the problem.

What to do About It

Given these particularly contemporary issues, I believe writers must become better educated on how to write for the voice in a more sustainable way. To that end, here are some points to consider when you’re writing your new musical.

Discuss each characters’ vocal type from the beginning.

When creating a breakdown of your musical’s characters, make sure to consider their voice types. You can also discuss with your creative team other vocal qualities you want the singer to have (i.e. a warm sound, more operatic, or less refined, etc.). Thinking of this early will help focus your picture of the character and make sure you’re writing specifically for a particular voice type. All this can certainly change, but if and when it does, it will be more likely to relate to the dramaturgy of your show.

It’s also helpful to think about different musical theatre performers you could see singing various roles. My colleagues and I are currently working on a new show in which a Laura Benanti kind of voice would be very appropriate. That information will help me as I’m writing music for that particular character.

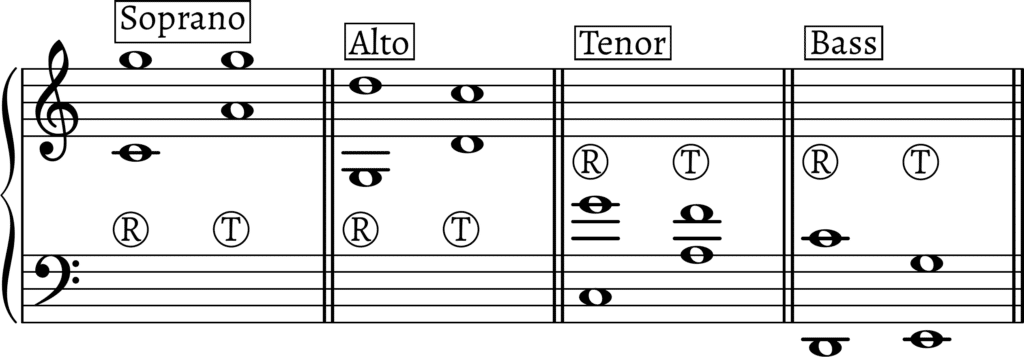

(R) Range and (T) Tessitura for voice types

Understand the difference between range and tessitura.

Simply put, range is the lowest to highest note in a song. Tessitura is where the bulk of a song lies. For instance, I can write a song for a baritone with a 2-octave range, but if the tessitura sits above their passaggio (where the voice transitions – i.e. chest to head register), the singer will be more likely to get tired faster.

A musical theatre performer is often asked to sustain a high belt/mix in or above their passaggio for too long. Over time, this can create vocal damage. There are many roles (especially for women), which have a high turnover rate because the kind of singing demanded by the writer(s) is not sustainable. It is also not uncommon for women to undergo operations to remove nodules from their vocal cords as a result of these shows. These nodules are essentially calluses on the very tender tissue of the cords, caused by repeatedly bringing them together in an aggressive way. Because women’s vocal cords are shorter then men’s, they are more susceptible to vocal damage.

Writers have a responsibility to understand how to create exciting scores without overly taxing the singers. It is completely possible to protect the singer while also demanding a lot of them. One great example is Jason Robert Brown’s writing for Kelli O’Hara in The Bridges of Madison County. He uses the full extent of Ms. O’Hara’s malleable voice from top to bottom without taxing her in any one area for a long period of time.

Avoid writing in and above the passaggio for long periods of time.

Related to the above, it’s important you know where each voice type’s passaggi (plural) are so they can avoid hovering in those areas. For instance, as a baritone, my voice switches twice: between E3-G3 (E through G below middle C) and again between A3-C4 (A below middle C to middle C). Mezzos have similar passaggi an octave up, though there are always variations.

Most singers work on smoothing out these transition areas on different vowels as part of the foundation of their technique. Yet, even the best singers will find it challenging if you spend too much time in and above their passaggio. Working with singers or even a voice teacher who can point out these areas of the voice can be incredibly beneficial to you as you write.

Consider when belt is appropriate.

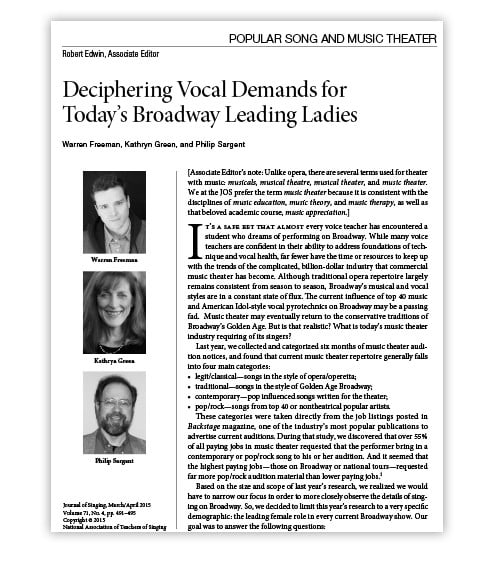

High belt/mix has become more popular on Broadway. In 2015, Warren Freeman, Kathryn Green and Philip Sargent wrote an article entitled “Deciphering Vocal Demands for Today’s Broadway Leading Ladies,” published in the March/April edition of the Journal of Singing. After reviewing audition listings for twenty-six Broadway shows, they discovered 85% of the leading female roles required belt or a belt/mix, some expecting the singer to belt as high as G5 (G above the treble staff).

I have no problem with high belt/mix – it can be a very exciting sound. I teach how to create that sound in a healthy way in my studio.

The issue I have with many contemporary writers is that they rely too heavily on belt to create dramatic and emotional tension in their work. As a result, everything ends of sounding of equal importance to the character, which creates subliminal confusion for the audience.

Belt is totally appropriate and exciting when used judiciously.

Consider the pace of the lyric.

One of the common issues I see in contemporary musicals is that there is often a lack of economy in the lyric. When this happens, the song doesn’t let the voice truly sing.

That’s not to say patter songs can’t be effective in contemporary musicals. They just require a higher level of craft. Consider Sondheim’s “Not Getting Married Today” from Company. The craft of the lyric is so exquisite because Sondheim took great care to make sure his lyrics could be sung and clearly understood at a fast tempo.

The pace of the lyric tells us so much about the character’s thought process. When the lyrics and music are well-paced, the singer will have a better chance at inhabiting the character through the song.

Clearly mark your scores.

When composers leave off dynamic and phrase markings, they ignore a considerable chunk of their work as a dramaturg. Dynamics (how loud or soft something is sung) are emotional clues for the performer. The way the score is marked can be of incredible insight to them when done well. It can also help them better pace the song so they have enough stamina to meet its demands.

Sing everything you write.

Regardless of whether or not you are a trained singer, you should sing everything you write for the stage. There’s something satisfying (not to mention telling) about how something feels in the voice. It also encourages the writer to work away from the piano, which I have found to be a helpful tool in creating music specific to a particular character or dramatic situation.

Work with several different singers.

I know many writers who create roles specifically with their voices in mind or that of other colleagues. That can be great, but it’s important we make sure our work translates well across many different singers if we want it to have longevity.

A couple years ago, I heard a song workshopped for a tenor, which sat so uncomfortably high for the singer, it was impossible to pay attention to the character’s journey. Sure enough, the composer had written it for his own voice. That’s all well and good but, assuming he’s not going to play the role, his options were going to be blessedly limited when it came time to cast.

Writing in extremes of the voice will not only create problems for the performer – it will also weaken the viability of your musical to be produced.

Why All This is Important

As writers, we have a responsibility not to normalize potentially dangerous vocal writing for the musical theatre performer. We must take into account what the voice (and, indeed, the entire body) is capable of recreating 8 shows a week, whether on a Broadway stage or regional theatre. It is the highest sign of respect to the performing artists, who bring to life our characters, allowing them to tell their stories in more powerful ways.

Adopting the above guidelines while we are creating our new works will not limit our creativity or hinder our potential in this ever-changing industry. Instead, it will force us to be more specific in our writing. And every musical can benefit from that.

Great Article! Very useful for me.

So glad! It’s an important thing to consider.

A great new article on Broadway News about vocal injuries on Broadway. Writers…take note!

“But the frequency of injury itself may only be increasing, as new musicals trend toward vocally-demanding pop, rock and belt-heavy scores. (“Look at Elphaba’s keys, and then look at the keys for Nellie Forbush!” Leung said.)”

https://broadwaynews.com/2019/09/19/speaking-out-about-vocal-injuries-on-broadway/

thanks for the information

Agreed, great article.

And if anybody is looking to write for baritones (wink wink), may I recommend–since it wasn’t on the range/tessitura chart–a comfortable range from G3 to about E4/F4, with a tessitura of C3 to maybe D4. But, hey, everybody’s different…

I’ll also note the increasing need for “bari-tenors”, and a growing infrequency of contemporary musical theatre scores using true basses and baritones (like said in another comment: comparing Wicked vs South Pacific). I realize some of this has to do with characters and storyline (e.g.: basses usually playing older and/or villainous characters, baritones playing leading man/”virile” types). Some of that might even be due to more contemporary scores being influenced by Pop, Gospel, or Rock, which favor three-part harmonies (no part for bass), and, in general, usually feature tenor or female belt.

It would be refreshing to see more writers, like you said, considering characters’ vocal types from the beginning. And also, maybe even being more open-minded about which vocal types can best serve in telling their stories and conveying character. And, of course, which musical style/genre a composer chooses will determine which vocal types will be used.