I enjoyed a delightful phone call with a new musical writer today. A long-time musician, she has set out to write book, music and lyrics to her first musical—at 71 years young!

While she felt comfortable with music and lyrics, the bookwriting portion has been more of a struggle. Her show is based on a historical event, which has its challenges. We talked through a few things that I hope to prove helpful.

I know we’ve all been stuck at some point or another, so I thought I’d share with those of you in the same boat, no matter what the context or genre of your story.

1. Define the story nugget.

Many, many steps ahead in the musical writing process is the need to “pitch” your show to potential producers, investors, theaters, artistic directors, and other significant players. We often wait until that time to work on our “elevator pitch,” a concise version of the musical’s story. However, being able to briefly describe the story from the onset can really help build the skeleton on which to flesh out your show.

Can you answer these 4 questions?

- Who is the Protagonist? Whose story is this?

- What does the Protagonist want?

- What (or who) is keeping them from achieving their goal?

- How does the Protagonist overcome that obstacle?

With historical events, there are a lot of people involved and tons of rabbits to chase. This has the potential to muddy the story waters, confuse the audience, increase the necessary cast size (and thereby cost), and a host of other problems that happen when we follow those rabbits into deep holes!

I highly recommend getting a copy of The Ultimate Musical Writer’s Planner and working through the first few sections on story structure and character development. This will help you explore new ideas, define plot points, and really trim and polish your story.

2. Consolidate characters if you can.

If the spark that lit your flame to write a musical came from behemoths such as Les Miserables and Phantom of the Opera, you may envision a robust cast with soaring vocals and orchestrations. That however, is not always the best way to get started. Now I’m a big advocate of go big or go home, but with musicals, it’s helpful to be able to start small.

First of all, it will help your story. Be sure you can identify your protagonist (see #1) so the show doesn’t become a loosely knit telling of many character’s journeys.

Second, it will help with producibility on the front end. Can you get by with a cast of 15? That is much more feasible to produce (or self-produce!) than a cast of 30. Can you carve it to 10 with doubling? Even better! Down the line when licensing for community theatres, schools, churches, etc., expanding the cast will be feasible (so the Jones triplets are all guaranteed a part!). But in development—and on the creative front—learning to work with limited resources is going to save you time, money, headache and heartache. Have two characters that could be combined into one? Go ahead and tackle that job now. Trust me—a director (or producer) will make you do it later. Do it now while you’re not under time-limited development pressure.

3. Consider a collaborator.

The writer I spoke with has a music background and felt most confident in her composing abilities. But since the subject matter and idea for the show was hers, she had also written the libretto. She said, “I’ve done the book, music and lyrics, and have, surprisingly, found the book to be, by far, the most difficult.”

When I asked about potential collaborators, her biggest obstacles were 1) where to find one, and 2) her fear of turning her vision over to someone else.

I’m sure we have all been in that very situation. How can we be sure that the burning story we have inside of us will be equally loved and shepherded by someone else? It feels vulnerable and risky—kind of like sending your firstborn to Kindergarten! But theatre is a largely collaborative genre, and your musical will benefit from strong creative external input.

Theatre is a largely collaborative genre, and your musical will benefit from strong creative external input.

Read: Collaboration Story: We Make Each Other Better

For those who want to go it alone:

If you’re going to do it all yourself (book, music & lyrics), learn as much as you can about those unique disciplines. Read musical writing books, take classes, seek a coach or mentor, and study other musicals. We also have great tools available such as the 7 Plot Points Worksheet and the Ultimate Musical Writer’s Planner. Be sure you get a script review from a professional after each rewrite so you can continue to fine tune your show.

For those who’d like to seek a collaborator:

If you’d like to work with a collaborator, make a list of what your strengths are, what is important to you, and what your vision of the show is. (We have a worksheet to help with that here.)

A few good places to seek out collaborators:

- MW Collaborator Classifieds

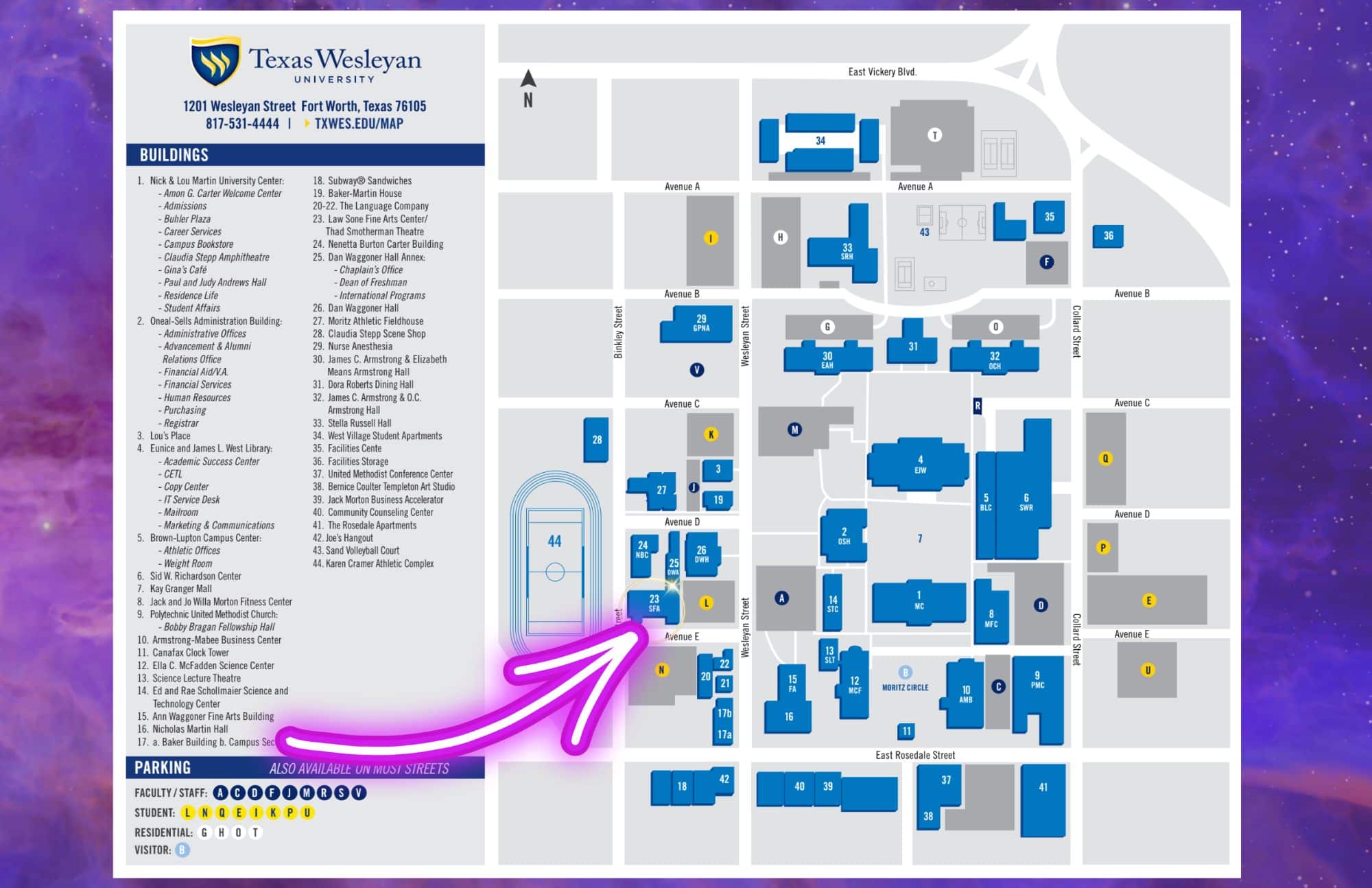

- MusicalWriters Academy

- Facebook Groups (I would suggest joining this one, this one, and this one to start.)

- The Dramatists Guild

Once you’ve found a few potential collaborators, do a trial song/scene together. See how things gel—how you work together, how your visions align, if your communication skills and personalities are compatible. If all is well, you might have found your partner!

When you’re really ready to work together for the long haul, get a collaborator’s contract in place. If you’re a Dramatist Guild member, they provide a full suite of legal docs. The Dramatist Guild legal advisors will also look over any contracts you have and make sure all looks correct—for free! I’ve had them take a look at several contracts which has saved me big bucks on legal fees. If you’re not a member of Dramatists Guild, I would suggest purchasing a copy of Business and Legal Forms for Theater, Second Edition by attorney, producer, and playwright Charles Grippo. You should find most of what you need in there to get started.

4. Always serve the story and the project.

I may sound like a broken record, but I’ll never stop stressing the importance of not being precious with your work. When a dramaturg wants clarification in one of your plot points, when a director doesn’t see the need in a certain song, when a producer needs you to cut your cast in half, or when a collaborator needs you to trust them about a song key or modulation, you have to learn to let go. If there’s something you just can’t budge on, that’s okay. But realize that resisting change or direction comes at a cost. It can cause a show to stop dead in its tracks and not be able to move another inch forward. It can also keep you from finding people to work with. Your reputation as an artist is important and delicate. Be sure the battle you pick is worth it. Just like a musical only gets so many “ballad points,” a writer only gets so many “battle points.”

Your reputation as an artist is important and delicate. Be sure the battle you pick is worth it.

Whether it’s how many storylines you have going, how many characters make the cut, or who you decide to be creatively involved with over the course of your writing journey, heed these words of wisdom from one of my all time fave movies: “You must choose, but choose wisely.“