History of Metaphor in Drama

When poetic lyrics or lines of dialogue paint vivid pictures for us, they not only move us emotionally, they become memorable. Romeo didn’t look up and say, “I must gaze at this beautiful Juliet above me in that balcony.” Instead, Shakespeare wrote words for him that we treasure centuries later: “What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.”

In this description of Juliet, Shakespeare utilizes metaphor, one of the prime tools of the writer’s craft. A metaphor is a literary device that figuratively compares and equates two things that are not alike. Standard metaphors (and similes, a subcategory of metaphor) make the comparison obvious, whereas implied metaphors compare two unlike things without actually mentioning one of them. Aristotle wrote, “The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor… and it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in the dissimilar.”

“The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor… and it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in the dissimilar.”

~Aristotle

Stephen Schwartz’ Pippin and Pocahontas – Metaphorical Favorites

Through the centuries writers have effectively employed sensory-rich metaphors to inspire and clarify. Broadway and film songwriter Stephen Schwartz has carried on the tradition and added his own spark. From whole-song metaphors like “Meadowlark” and “Beautiful City” to the nature-inspired similes of “For Good,” Schwartz is a master of imagery-filled lyrics that represent an emotional journey.

In an interview over lunch, I invited him to reflect on making metaphors and offer any advice for fellow musical writers. The following are highlights from our conversation, edited for clarity. (For more stories and songwriting ideas, please see my Stephen Schwartz biography Defying Gravity, now in an updated second edition.)

Composer-lyricist Stephen Schwartz and biographer Carol de Giere discuss metaphor over lunch June 11, 2021.

In terms of songwriting, Stephen Schwartz described metaphor as a helpful tool in writing lyrics, giving writers something to say while adding a poetic quality. His first thoughts were about pop songwriters of the 1960s and 1970s who had inspired him as a developing writer, for example, Paul Simon. “You don’t necessarily know exactly what he’s saying from a literal point of view, but from an emotional or subtextual point of view you get it. And I think that’s also true of Laura Nyro.”

He then reflected on two of his most renowned lyrics with this emotional quality: “Corner of the Sky” from Pippin and “Colors of the Wind” from Disney’s Pocahontas, and how unexpected connections contribute to their power. “There’s no such thing as a corner of the sky and the wind has no color—but it’s precisely because of that that I think the listeners appreciate what the character is feeling and what he or she is trying to say. Everyone knows what ‘Gotta find my corner of the sky’ means even though there’s no such thing as a corner of the sky, and everyone understands the meaning of painting with all the colors of the wind, even though the phrase doesn’t make literal sense.”

The lyric lines in these songs connect abstract qualities with visual images. In “Corner of the Sky,” the character Pippin equates his abstract youthful ideal of his place in the world with a sky image. In “Colors of the Wind,” Pocahontas, using the image of winds of varying colors, portrays a broadened view of the natural world than John Smith’s Eurocentric view allows.

Inside and Outside Metaphor Observation

We next turned to his experiences writing new lyrics for “Beautiful City,” a Godspell movie song that he rewrote in 1991 after the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles. It’s a good example of using observation, in this case gained from media coverage, to find material for an extended metaphor. I commented, “You took specific words that happened to be related to rebuilding after the riot and wrote a building metaphor.”

Stephen said, “There were literally ruins and rubble, and there was literally smoke. It was all over the news, what was going on in South Central LA. So I began with that—almost a literal image of the corner of Florence and Normandie, these images of urban destruction. And out of that, the city could be rebuilt both literally but also psychically—emotionally. I think you can call the title phrase ‘We can build a Beautiful City’ a metaphor because everyone who hears the song knows that it’s not literally about building, even though there are lyrics about bricks.”

Quoting the lyric, I added, “Brick by brick, heart by heart.”

Stephen continued, “I think this is true of all writers—so much of what we are doing is instinctive. We’re not planning it out in advance, but at the same time, it’s a deliberate choice. It’s deliberate enough that in retrospect I can have a conversation like this with you and say, ‘That’s why I chose these words.’ What one writes doesn’t really happen by accident, but it happens by drawing on your unconscious and the decisions and choices your unconscious is making.”

We then looked at “Children of the Wind,” an anthemic song from the Broadway musical Rags set in America in the 1910s with music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Stephen. In the piece, the lead character Rebecca sings of herself and her fellow immigrants in the lines “We’re children of the wind/Blown across the earth/Pieces of the heart/Scattered worlds apart….”

Stephen said, “I think it’s great in talking about the value of metaphor that you specifically chose ‘Children of the Wind.’ The final version used in the show was my third lyric try for that melody, and the previous two that did not work were much more literal. One version was called ‘I Will Find the Way’ and it contained straightforward lines like ‘I will find a way to you.’ What she was singing about was literally the story, but it wasn’t effective because it was just the story. It was only when I abandoned that approach and said to Charles, I need to be more poetic and, in fact, more metaphorical, that the song worked. That was such a lesson to me because once the lyrics were right, then all that anyone talked about was how great the music was. And that’s what you want as a lyricist. Even when I’m only providing the lyrics, my goal is that the lyrics will help the music to realize its emotional potential and then that’s what people will notice.”

Extending the Imagery

Another example I brought was “Spark of Creation”—a piece from Children of Eden sung by the character Eve about her discovery of creativity. I pointed to all the fire images and noted, “The whole thing is a metaphor because we don’t literally have fire in our blood.”

Stephen replied, “When I started writing the song and trying to put myself into that feeling that Eve has of excitement and anticipation, I just felt like my fingertips were tingling. And that’s why the first line was ‘I’ve got an itching in the tips of my fingers.’ It could have been ‘tingling’ now that I think of it, but that was the word that came to me first, plus ‘itching’ is easier to sing. So that was a literal feeling and the rest of it flowed from there, but that was my way in.”

I asked, “Is there something you can say about continuing to look for the metaphors? Because you’ve got (on different lines) ‘boiling,’ ‘burning’, ‘spark,’ ‘blazing,’ and ‘fire.’”

Stephen said, “The metaphor is of fire as an expression of inspiration and creativity. That’s not a new idea obviously—’the creative fire.’ But then in writing about it, I just wanted to keep that image going. Later she says, ‘The spark of creation/may it burn forever…/I am a keeper of the flame.’ The fire image goes through the song because the title demands it. We’ve talked about this before: starting with a title and letting the title determine a lot of what the rest of the song should be.”

Metaphor Creates a Freshness Factor

I asked Stephen, “When is it a good idea for writers to use metaphor and imagery?”

That’s when he dove into the topic from another angle. “One of the challenges one faces in songwriting—it’s why I find love songs so difficult to write—is that everything has already been said. There’s almost nothing you can write that hasn’t already been written. Those ideas have been expressed before, the emotions have been expressed before. So a challenge is how do you express an idea in a fresh way, so it doesn’t sound stale and tired and trite? And how do you express it in a way—and this is the additional task of musical theatre writing—how do you express it in a way that comes from the character? The use of imagery is very helpful there.”

He mentioned to me again about his little piece of advice he uses for himself and offers to other songwriters: “In lieu of inspiration, do research.” He collects books, poems, articles, and recordings related to his projects, and when possible, he goes on field trips. Disney had sent him to Jamestown in Virginia for Pocahontas as well as to Paris for The Hunchback of Notre Dame where he visited the Cathedral at the center of the movie so his imagination could be lively with local imagery. He continued, “What I’m doing is trying to see through the characters’ eyes. So I like to do research as to what kind of trees grow in this area, and what are the names of the birds – what is around the character in his or her daily life? What is the environment of the character that he or she just takes for granted?”

I said, “Maybe you’re collecting sensory details: what they would see, hear, smell…”

He confirmed, “Exactly. You’re collecting sensory details. And if you have a list of a hundred of these, maybe four of them will find their way into lyrics, but yes that is a way of being the character.

I asked, “There’s good reason to make lists—they’re not a waste of time?”

Stephen replied, “Oh no, [not a waste]. I start by making all these lists of sensory details, of possible rhymes, and then I don’t use most of them, but I have them to draw upon. Alan [Menken] talks about creating a palette for each score he is working on. You know, when a painter is going to start a painting, (not that I’m a painter), they make color choices. They don’t work from every single color under the sun. They create their palette, and that’s what one is doing as a writer. Alan does it as a musician. When I’m approaching lyrics, I’m giving myself a toolbox, so to speak. What can I select from?”

I said, “A toolbox! Nice. A metaphor!”

In our discussion of metaphor, of course I brought up “Meadowlark,” his story song from The Baker’s Wife that is known best from the many concert performances or cover versions on albums like those of Patti LuPone, Liz Callaway, and Betty Buckley. In this unusual song, the character even realizes she is exploring a metaphor, in the sense that she is telling a story that she’ll use to reevaluate her own predicament.

Stephen said, “For ‘Meadowlark,’ the entire song is a metaphor, basically, until finally at the end, the last verse describes literally what is going on.”

He didn’t elaborate further during our lunch interview but has previously described the writing of this song for the character Genevieve. He explained in a website Q&A that the metaphor for “Meadowlark” represents “a story about someone who does what she knows is the ‘right’ thing to do, but then it breaks her heart, and she literally cannot live with the choice….As I was thinking about her expressing the emotions she was going through and feeling them myself as I began to write, this story more-or-less popped into my head.” He remembers it being influenced by several familiar children’s stories, including Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor’s Nightingale.” (For more detail on how he arrived at the song, see the Schwartz biography, Defying Gravity.)

Similes, Too

After looking back at my song list, we conversed about his famous ballad for Elphaba and Glinda, “For Good,” from Wicked, which is filled with similes—the specific type of metaphor that uses “like” or “as.”

Stephen said, “What I had going into ‘For Good’ was this great title that came from a conversation with Winnie [Holzman], and then the conversation I had with my daughter about her relationship with a lifelong friend, which very specifically defined an attitude toward this kind of relationship. And then the rest of it was similes.

“When I work with translators for ‘For Good,’ I often see them struggling to translate ‘Like a comet pulled from orbit’ into Danish or some other language, that is a literal translation of the specific similes I used. I tell them: ‘All you have to do is pick images of something that has an effect on something else. I don’t care what the images are, you have to illustrate the central idea—because I knew you, I’ve been changed—that’s what you’re aiming for. So you have to find images of things that cause a change in other things, but you don’t have to use the same images I did.”

He added, “Lyrics are often written backwards anyway. You need to know what you’re aiming for and then get there in an artful way that doesn’t look like you’re struggling to get to your destination. And metaphor, simile, any poetic device that uses imagery is a very useful tool to accomplish that.”

Lyrics are often written backwards anyway. You need to know what you’re aiming for and then get there in an artful way that doesn’t look like you’re struggling to get to your destination. And metaphor, simile, any poetic device that uses imagery is a very useful tool to accomplish that.

~Stephen Schwartz

(Although we didn’t discuss them, other examples may be found in Stephen’s works. His Pippin song “Glory” features numerous similes that suit the character Leading Player at that moment in the show, as the character sings of war and swords: “Steel is cold as moonlight,” and so on. The metaphor-rich Children of Eden song “Hardest Part of Love” also includes the simile “Like an ark on uncharted seas, their lives will be tossed”).

Metaphor as a Window into a Character’s World

We talked next about “Through Heaven’s Eyes,” one of my favorite songs from The Prince of Egypt, used in both the movie version and later stage version, in which the Midian priest character Jethro encourages Moses to take a broader view of his life and worth. We discussed Stephen’s trip to Egypt and how he had seen mountains in the Sinai desert that looked like big piles of rocks before he wrote the lyrics: “And the stone that sits on the very top/Of the mountain’s mighty face/Does it think it’s more important/Than the stones that form the base?”

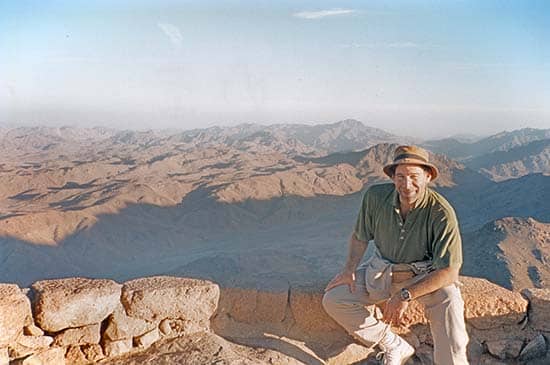

At sunrise, Stephen Schwartz and colleagues climbed up Jebel Musa, the peak traditionally known as Mount Sinai in the Sinai Peninsula.

Stephen noted, “Again the whole song is a metaphor. Basically, what Jethro is saying over and over is: You don’t have the bigger picture of where your life fits in the grand scheme of things, so you can’t dismiss yourself as being worthless—you have no idea. That’s the story of the song. From there, how do you say it? You can say it in one sentence as I just did, but then you have no song!”

We both chuckled.

He continued, “So how do you express that in a way that feels musical and vivid? One uses metaphor. So what I did was consider the character who sings this—what does Jethro see every day? He wouldn’t use a metaphor about a busy city street.”

“Taxis,” I suggested.

Stephen continued with a gesture toward a make-believe line of taxis, “He wouldn’t say ‘One taxicab doesn’t know where the fleet is going.’ Or ‘Does a car in a train think about where the whole train is going?’ Those images don’t belong to him. So you limit your imagery to what comes naturally to the character. We talked about stones on mountains. That’s what you see in that kind of desert landscape—stones on top of stones. And he talks about a tapestry because that’s what they have, and a lost sheep, and so on.”

“….limit your imagery to what comes naturally to the character.”

~Stephen Schwartz

Word Choice and Emotions

The images in the Pippin song “Morning Glow” work in a similar way as a metaphor. In literary terms the song lyrics provide a symbol for the transformed, hopefully improved, society that would emerge under the rulership of Pippin. I included it in my discussion with Stephen because it’s such a beloved song.

Stephen said, “The phrase ‘morning glow’—what he’s singing about is bringing a new hopeful change to society and to himself.”

I asked, “When you were first thinking ‘morning glow,’ did you imagine a sunrise?”

Stephen said, “Kind of, but I wasn’t really thinking that literally. It’s just—what suggests a new beginning? And hope and promise and possibility? And so, ‘morning.’ To me ‘Morning glow’ is a more poetic image and has more emotion than ‘sunrise,’ which is a more prosaic word.”

I wondered if we’d hit upon a universal lesson for musical theatre writers. I suggested, “Maybe we can say that as a general principle, what you’re looking for is to evoke…”

“Emotion,” Stephen filled in. “That’s correct.”

“So rather than look at the literal words,” I continued, “we look for what is going to evoke the most emotionally for the audience. Is that a good principle?”

“I think so,” Stephen replied. “I think there’s a difference between musical theatre writing and what Paul Simon is doing or James Taylor or pop songwriters, where they don’t have a storytelling responsibility. It’s why it can be hard for the best pop writers to adapt to writing for musical theatre, because it goes against what they are doing at their best. I think for those of us who write musical theatre, we’re trying to fulfill our storytelling responsibilities, but at the same time evoke emotion with the words we select to tell the story.”

Stephen Schwartz has a treasure trove of experiences to draw from in conversation, but he also has meetings to attend (mostly on Zoom these days), songs to write, and family responsibilities, and so for now, we wrapped up. Before finishing our lunch, he and I also savored a limoncello gelato, frozen dairy drizzled with a lemon liquor syrup that was an odd combination but very satisfying. It reminded me of the way metaphorical language can pleasingly connect disparate experiences.

See the 2nd in this series: “By the Light of Metaphor – Part II: Improving the Odds of Making Good Metaphors and Images” (more perspectives and specific tips on enhancing our chances of writing good metaphors)

See Defying Gravity: The Creative Career of Stephen Schwartz, from Godspell to Wicked, Revised and Updated 2nd Edition for more stories.

Thank you Carol. I was led to you through Marty Rhona. Godspell changed my life. I went from the original Australian production of Jesus Christ Superstar to touring with Godspell, I was understudying all the female roles so learned more of the songs. Recently I heard a wonderful young actor who played Riff in West Side Story on the Sydney Opera House stage sing Beautiful City and it took me back to the mid seventies when I was with Godspell.

Thank you for insightful observations on Stephen’s take on metaphors. Your realisation of the journey of the senses brought me to the emotions within the human experience. Devotion speaks to me in a First Nations chant ‘spirit of the ocean. . depth of emotion.’

Could I ask you about your Godspell book that Marty showed and how to get a copy?

The First Nations I have been honoured to walk beside speak of the Star Nations and I have written a song from my love of Australia where the Star Nations are referred to in my first line. The song is called‘Australia Calls Us Home’ snd it’s on utube.

Thanks again for sharing your insights with me.

With wonder and awe.

Evie Pikler

Evie, thanks for the beautiful comments! You can get Carol’s book “The Godspell Experience: Inside a Transformative Musical” on Amazon here: https://amzn.to/2TXMjb0

Best!

Holly