All design descriptions written by the playwright must be as meticulously constructed as the dialogue. We must provide enough information to cue the designers, but not so much that their creative instincts are hamstrung.

Control freaks. All playwrights suffer this role to some extent. After all, we literally put words into another person’s mouth, move them in and out of scenes, and even specify many of their emotions. We are used to being fully in charge of the worlds we build on paper because…well…we are their creator. We have concepts in our heads of what our plays look and sound like on stage. Good for us, for as one of my MFA professors taught me, the more specific we are, the more universal our work will be. Be careful though, for the magnitude of our design descriptions could alienate stellar industry creatives. Why? Because we aren’t leaving them enough room to freely exercise their own craft; a flaw that can prove detrimental to development and production of our work.

When a playwright drafts a script, whether for a musical or straight play, she is limited in her delivery of information simply by the nature of dramatic work. Our audiences don’t have the luxury of reading our written design descriptions of the elements we imagined. Also, they don’t have the option to put the performance down and then pick it up another day at their leisure. Our work is confined by time and place. Audiences will sit happily for a couple hours or slightly more but after that, they generally want out. It’s challenging.

The Design Collaboration

So how do we convey the sensory elements of our story? We do so with a team, for we are not alone in our storytelling. Collaborative designers join us in transforming the words on a page into live performances that live in their own world. Collectively, our tools for doing so are dialogue, set, lighting, sound, and costumes. By purchasing tickets to a performance, audiences are indicating that they are willing to suspend reality for a bit. They will accept appropriate theatricalities that are surreal, suggestive, and even overt. It’s an unspoken agreement. Yay, theatre!

This is why all design descriptions written by the playwright must be as meticulously constructed as the dialogue. We must provide enough information to cue the designers, but not so much that their creative instincts are hamstrung. If that happens, our beautiful portrait of a story simply becomes a one-dimensional paint-by-numbers assignment for the designers. Of course, if the design specifics are essential to the integrity of the story (i.e., a door described as red in the script is referenced by characters as the red door), then they should be maintained. For general descriptions however, the writer must leave breathing room for designers to flex their own creative muscles. If we don’t respect their imaginations and craftsmanship, no worthy designer will be interested in our scripts.

When writing a scene, most playwrights have specific images in their heads regarding what the set, costumes, and props look like. If a character was inspired by the writer’s great Aunt Clara, who was always freezing and always wore a tattered yellow sweater, he may intuitively want to specify that the character wears a tattered yellow sweater, but if that detail isn’t relevant to the story, he may want to consider losing it and simply specify that she wears a sweater. If a character is cowardly, then a yellow sweater could serve as metaphor that signals the audience. In either case, we as writers must give our designers the liberty to work with us to develop their own concept of the sweater. This demonstrates our confidence in the designer’s competency as well as in our own work. The same rule applies to sets, sound, and lighting. We must give our designer a launchpad for their own work, providing just enough specificity to unleash their creativity, not so much that we weigh it down. It’s a fine line to straddle, but an important one to respect.

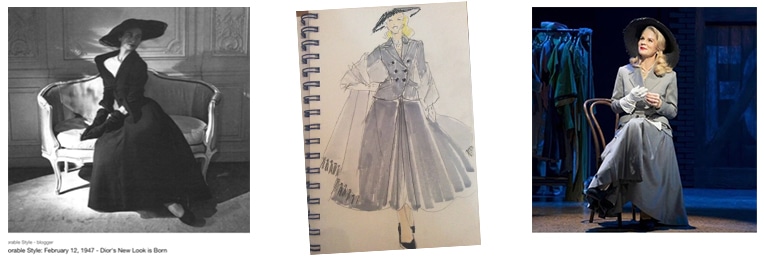

Left: Inspiration from 1947 Dior. Center: Jeff Mahshie’s sketch. Right:

How much design description is too much or too little? I asked the experts.

So, how much description is too much or too little? At what point is the playwright robbing a good designer of the opportunity to assert their own creative license so that they too can flourish artistically? To find answers I spoke with award winning costume and set designers Jeff Mahshi (NYC) and Steve Schepker (New Orleans), respectively.

You’ve both been designing shows for decades. When you read a script, what elements of design descriptions inspire you? What makes you chomp at the bit to get started designing a show?

JM: It usually begins with dialogue. In addition to being a costume designer I began my career and continue to work in fashion. There is a line in Kiss Me Kate where Lily, the female lead references her “Dior New Look Mink.” The moment I read this my eyes lit up. The Dior New Look was a huge turning point in fashion; it was presented in 1947 post war and was the antitheses of Prewar posterity. This musical was written in that year and the fact that Lily wears The Dior New Look speaks volumes about her character; the fact that she shops in Paris for her clothes, that she can afford couture clothes from Paris…and we have only scratched the surface.

SS: My mentor always said, “the two best days in a designer’s life are the day you start a show and the day you open a show.” He is exactly right. I’m excited at the start because I don’t know the solution. How do I best help tell the story? That’s what makes me want to start a show.

Sketches by Steven Schepker for Puffs by Matt Cox at Columbia Theatre

Conversely, what hits you in the face as restrictive or confusing?

JM: When the design descriptions are too literal, like a character wearing a Harvard sweatshirt if the character went to Harvard. Initially, I found scripts in general confusing. I have a good friend who is an amazing actor who used to read plays to me in the different characters’ voices. She realized I was hearing it all in one voice, so I highly advise to make friends with multi-Tony award winning actors 😉

SS: I really don’t find many things restricting. Recently, I’ve been working in many small theatre spaces and non-traditional venues with tiny budgets. Small spaces or tiny budgets aren’t limitations, they are opportunities. That sounds cliché, but it allows you to distill the ideas down to simple, hopefully elegant, solution. It all goes back to telling a story.

Steven Schepker sketch of Baby Doll by Tennessee Williams for Le Petit Theatre. Big Easy Award for Best Scenic Design

How do you approach initial design proposals?

JM: I read the script through a few times, then take notes. I also try to read any original source material. For example, if the play/musical is developed from a short story or a book, I read it through. Next step is meeting with the director.

SS: Obviously, I start with the script. Lots of reading. I like a hard copy so I can write in it. Notes. Thoughts. I also like to use a ton of images. Many designers don’t like Pinterest, but I find it the best for a variety of imagery. I share them with the director and other designers, and it gives us a place to start.

How do you integrate your process with that of the director?

JM: Communication is the key. I listen to their vision for the project; realism, minimalism, stylized…and then I ask any questions I have. Depending on the relationship, I can occasionally make a suggestion regarding the tone/look of the overall production.

SS: My processes with directors appear to be becoming more streamlined. We meet. Discuss. Decide on a direction and go. Many of the directors I work with are doing multiple shows on top of each other. The tradition of all of the designers coming together at multiple meetings and collaborating seems like a distant memory.

Have you ever designed a show in which you and the director couldn’t agree on your design? How do you manage that sort of conflict?

JM: Never. Telling a story is collaborative. I have always managed to find a solution and, honestly, when reworking a design, my experience has been that it’s always worked out. I think it’s important to keep an open mind. I’m always interested in pushing myself to make something better.

SS: I designed a Sweeney Todd and luckily had 18 months of prep time. It was great. I had tons of time for percolating, research, sketching and finished drawings. After a few months, I decided that I didn’t want to use “the cube”. The cube is the turntable solution used in original Broadway production. I was going to come up with a different solution and designed a series of slip stages and portals. During my presentation to the director, he was pretty hesitant, but we’d done a few shows together, so he trusted me. After more persuasion, he signed off. Flash forward to the third night blocking rehearsals, he called me in to watch. It was painful, all of the blocking was flat. His entrances were repetitious and predictable. So, with less than a month to go, we chose to completely redesign and adapt to a variation on the cube. Three long days later, we created a solution that was super functional and served the production. The director added a few more tweaks and we went exactly where I didn’t want to go. The show is still in my portfolio. I just hope I won’t be designing Hamilton in 20 years.

Do you prefer to interact with the playwright at any point in the design process, or do you stick to the director? Why?

JM: I feel this answer is definitely specific to me. Shortly after I began designing costumes, I started dating a director, so my training was “the director is the storyteller and it’s your job to help facilitate the storyteller.” The concept of the playwright in the rehearsal room has become more common of late. Initially, I rarely met them. However, the ability to interact with the playwright is a valuable luxury. I remember when designing Angels in America I was seated at the rehearsal in between the director and the iconic playwright Tony Kushner. After I got over my initial intimidation, the ability to ask questions—not just about design but about the play—was one of those rare unforgettable experiences.

SS: I am very lucky to work in an environment where we do at least one premier a season. This year, I’m doing two new shows. With that, I haven’t talked to a playwright in the pre-production process in decades. To put that in context, George H.W. Bush was in office.

Tell us about your proudest moment in designing shows and why you feel that way.

JM: There is a moment, usually after the first or second preview, when you are sitting in the back row of the theatre with the other members of the design team, assistant at your side, and you watch the production and realize every look, down to every earring, cufflink, etc., you have literally selected, touched, or designed. No notes. Lock it.

SS: I was asked to step in on Baby Doll, by Tennessee Williams, after the scenic designer had left suddenly. There were a couple problems; I only had seven days and had just accepted some fabrication work that required 40 hours of time with an hour commute each way. I quickly went into grad school mode and worked all day and drew into the night. Commutes were a good time for right brain problem solving activity and production meetings. Seven days later, I submitted a drawing package to the director and the shop. The show really fit in the space and earned a Big Easy Award for Best Scenic Design.

Any final words of wisdom for playwrights regarding design descriptions?

JM: A starting point is always helpful; something as small as a color suggestion or the specific town they live in. When designing Giant, there were very few cues. The movie version—untrue to the period—favored a 50’s silhouette that was flattering to the star, Elizabeth Taylor, but wouldn’t work for this production where the set was incredibly stylized and relied on the costumes to lead you from the 1900s-1950s. I was guided to the original Pulitzer Prize winning novel by Edna Ferber. There was one scene where she describes Leslie’s trousseau all in dove grey (unknown to me). This was not uncommon as it was supposed to make the newly pure bride a more sophisticated portrait of a married woman. She also uses almost an entire chapter to describe Leslie’s evening clothes and style as so simple it’s almost plain but worn with a brooch the size of your fist. I’m paraphrasing but she spends many pages on how Leslie looks all the while leaving plenty of room for interpretation.

SS: I want design descriptions somewhere in between Tennessee Williams and David Mamet. I don’t need to know how someone delivers the line. I prefer a short descriptive paragraph about the environment or how the space feels. I’m currently working on a production of Summer and Smoke, more Tennessee Williams. Tennessee’s stage directions, “As the concept of a design grows out of reading the play, I will not do more than indicate what I think are the most essential points.” His “essential points” are then followed by almost three full pages of details. In grad school, someone told me that stage directions should be like a negligee. It’s a sneak peek. A preview. You don’t need the whole thing but just want more.

Donna Gay Anderson is a playwright/lyricist whose musicals and plays have been developed and presented in New York, North Carolina, Louisiana, and Kentucky. Her musical, High and Mighty, received multiple awards of recognition at the Kennedy Center American College Theatre Festival. She was the winner of the So You Think You Can Write One Act Competition and was a finalist in the one act play category at the Tennessee Williams New Orleans Literary Festival. Her work has been presented at the First Draft Series at Chicago Dramatists and also by artists from Kentucky Shakespeare in partnership with Spalding University in Louisville. Currently she is collaborating with composer Theodore Christman on the musical Unfolded, inspired by the life and work of Susie Krabacher. Her newest play, The Way We Say Goodbye will premiere at Southeastern Louisiana University in November 2022. She and her husband Tom live in swampy Louisiana with any stray dog who wishes to spend the night.

Steve Schepker is a Professor of Theatre at Southeastern Louisiana University where he oversees scenic and lighting design for all theatre productions. Professor Schepker’s classroom teaching includes Introduction to Theatre, Stagecraft, Scenic Design, Lighting Design and Play Production courses. His work outside of SLU includes scenery and lighting design for The Tennessee Williams Theatre Company, Le Petit Theatre, the NOLA Project, the Marigny Ballet, Pensacola Opera, Shreveport Opera, Pine Mountain Music Festival and the Tennessee Williams Literary Festival. He also designed television sets for WYES and WLAE in New Orleans and the Southeastern Channel. Most recently, Steve has received a Big Easy Award for Best Set Design for Baby Doll at Le Petit. At Southeastern, he was awarded the Southeastern Louisiana University President’s Award for Artistic Excellence. He has also received multiple American College Theatre Festival Excellence in Design Awards for both scenery and lighting. Professor Schepker holds an MFA in Scenic Design and Lighting Design from Western Illinois University and a BS in Theatre and Mass Communication from Lindenwood University. www.steveschepker.com

Jeff Mahshie. Broadway: Kiss Me Kate, She Loves Me (Tony and Drama Desk nominations. OCC Award), The Terms of My Surrender, Next to Normal, The Little Dog Laughed. Off-Broadway: Hurlyburly (Drama Desk Nomination), Privilege, Some People, The Scene, The Little Dog Laughed, Becky Shaw, Next to Normal, Gruesome Playground Injuries, The Corn is Green, The Kid, Giant, Marie and Bruce, Laughing Wild, The Unavoidable Disappearance of Tom Durnin, Evening at the Talk House, Good for Otto. Follow @jeffmahshie