Chapter 9 in Jack Viertel’s book, The Secret Life of the American Musical, focuses on the Broadway “star.”

What is a Broadway star?

From a pragmatic perspective, a Broadway star is an actor or actress who warrants a higher salary because they can almost guarantee to put butts in seats. They’re the names we recognize and are willing to buy a ticket to see, sometimes disregarding the musical’s inherent creative qualities or success.

But we all love them, right? They’re something special.

Viertel quotes casting director Jay Binder about Broadway stars:

“A star comes out onstage and every member of the audience feels that the star has a secret that is shared only with them. The star is looking directly at them saying, ‘You and I know something no one else in the room knows.’ That’s what’s mesmerizing. And they do it to fifteen hundred people at the same time.1”

Viertel discusses several musicals that rode on the involvement (and demands) of a star, citing Ethyl Merman as the prime example in her day to forward the success of shows such as Annie Get Your Gun and Gypsy.

Most of us, at the stage we’re at in our musical writing, are not going to have a Broadway star in our workshops, readings, and even regional premieres. So how can this chapter apply to us?

I have a few suggestions.

Give your characters star-quality, but don’t depend on a star.

Even if you’re early in your musical writing career and can’t imagine a Broadway star ever being part of one of your productions, know that you are creating a potential incubator for a new star to be born. Viertel describes how Julie Andrews—a young and aspiring actor—was given multiple opportunities to show her skill and charm as the scenes of My Fair Lady progressed. By the end of the show, the audience was mesmerized, and a new star was born.

Does one of your characters have the potential to cast a star?

If so, great. But—the show should be able to succeed without one. Make your characters unique, three-dimensional, relatable, and extraordinary. Give them a larger-than-life want, and an even greater passion to achieve it.

Create characters that the audience will fall in love with, and they’ll follow you anywhere. Let the show stand on its own merit. If a star joins in the future, you’ve got a huge bonus. But don’t depend on the star.

Is Idina Menzel a star?

Totally.

Does Wicked depend on a star?

Nope.

If the actress playing Elphaba has the chops and the heart, we’re gonna love her. Because we love Elphaba.

The character grabs us first, not the actress.

I’ve seen Idina in a couple of other shows that didn’t fare so well. They might have soared with her at the helm if they were strong shows to begin with. But the presence of a star does not a hit show make.

Great writing is where it’s at. Every time.

Your protagonist is your “star.” Let them shine!

Viertel lists these opportunities for the star (or your protagonist) to sing:

- Opening number

- I Want song

- Conditional love song

- Act I solo

- First act finale

- Production number in Act II

- 11 o’clock number

That’s a lot of songs for one person to sing, so try to balance that with a variety of other characters’ songs.

Use a “stand-in star” when creating your characters.

Sometimes it helps from the very beginning to have a certain actor or actress in mind when developing out your characters.

Who would be the ideal person for that role? Just imagine the Genie from Aladdin is your casting director.

They could be a stage or screen actor, currently working or long-time deceased. This is your “type.” Whether or not the actor would be able to fill the role is not important. It’s just a tool to help you develop out a solid three-dimensional character. Is this character a perfect fit for Burt Reynolds? Carol Burnett? Ben Platt? Kristin Chenoweth? Find someone as your “stand-in star.”

Viertel notes that Miss Adelaide—and her songs— in Guys and Dolls was built around the performer’s unique personality, strengths, and interests. Similarly, Kristin Chenoweth’s origination of Wicked’s Glinda created a uniquely “Kristen” character that actresses since have closely modeled.

Before Broadway star Kristin Chenoweth was cast as Glinda (Galinda/Glinda), “the part was a much more peripheral figure,” says Wicked bookwriter Winnie Holzman. “Based on wanting Kristin to do the show, and how much we felt she brought to it, we started to reshape the whole plot. It became the story of a friendship. That happened because of Kristin….”2

[icon name=”question-square” class=”icon-1.5x”] What other characters were originated by actors who left a lasting impression on the role? Share your examples in the comments section below.

Good shows will draw in the stars.

Broadway stars are great for marketing and can sell a show on their own—as long as they’re in it. But they can be a crutch. Write your show in a way that the star will come looking for you (not you go looking for a star)!

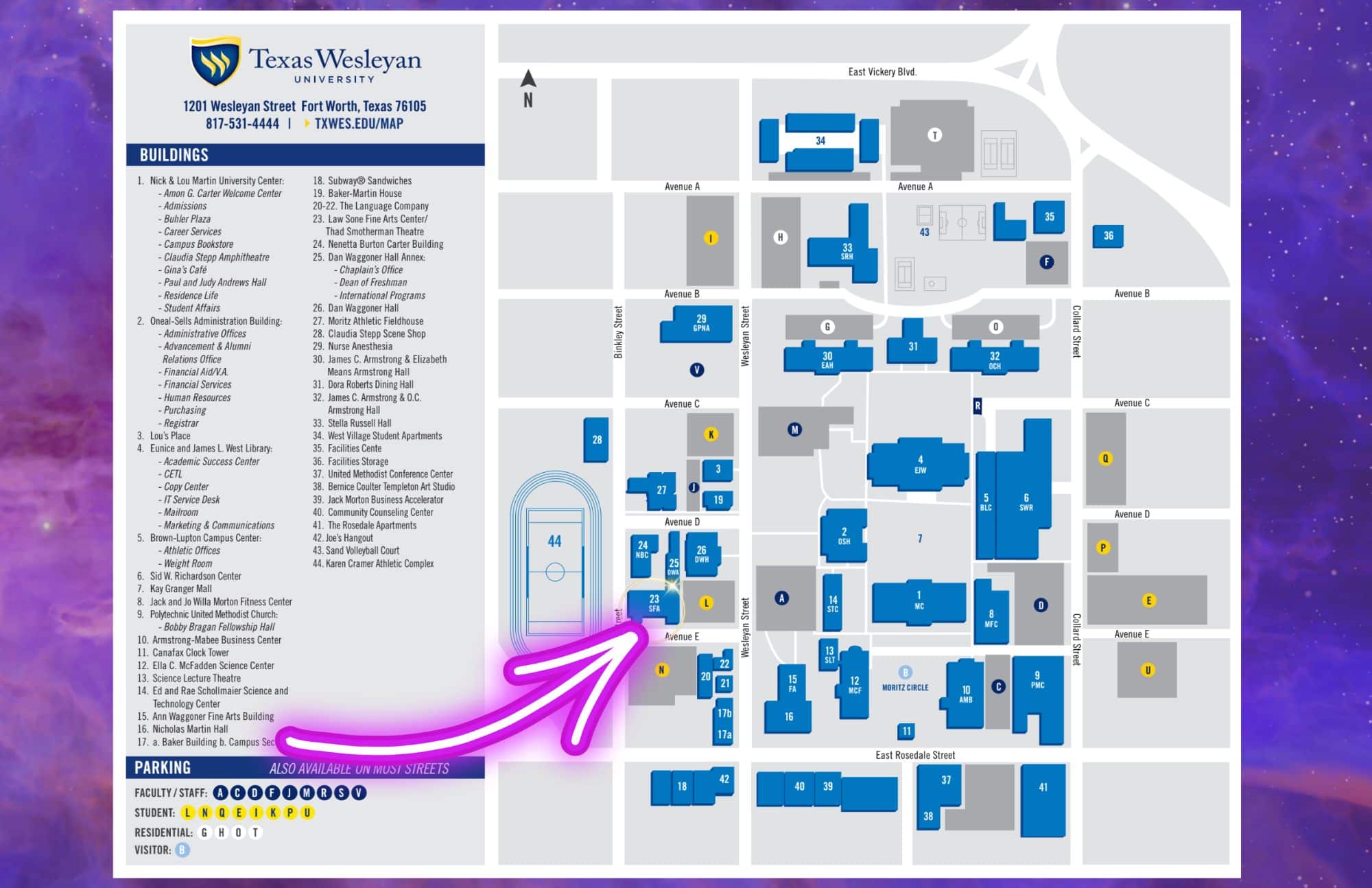

It is wise, however, to always cast the best talent available. In early development, you need someone who can take a role and fill it out with smart, connected acting choices and vocal excellence. How do you draw in those actors to readings and workshops? Get that elevator pitch solid.

(On a production note, be sure to provide clear vocal ranges, character “types”, and any distinguishing characteristics in your list of character descriptions.)

Create great characters and a great story, and sell it!! Let your show be the star!

Coming up next: Chapter 10, “Tevye’s Dream”

In this chapter, Viertel is writing about a Broadway that used to exist, but no longer exists. The most recent star vehicle I can think of is Fame Becomes Me, which opened 13 years ago and starred Martin Short. It wasn’t a hit, but the people buying tickets were already Martin Short fans and had a reasonable expectation they’d see Short do what Short does best. That’s a star vehicle.

Stars still exist, but none of them are willing to commit to spending enough time on Broadway in a new work, for the show to recoup.

Some of my favorite shows – Sweet Charity, Bells Are Ringing, Wonderful Town – are star vehicles, and I always wanted to write one. So, I did; by redefining “star.” I was creating a musical comedy for a tiny subset of New York theatre – the improv community. We cast three of our leads with a trio of comedians well-known within those circles, and anticipated they’d draw an audience used to shows made up on the spot. Now, I knew their talents well, knew things they were good at, knew how to use their brass, their fragility, their goofy idiosyncrasies. The audience got to see performers they already loved doing the things they loved them doing; and I got to write a star vehicle.