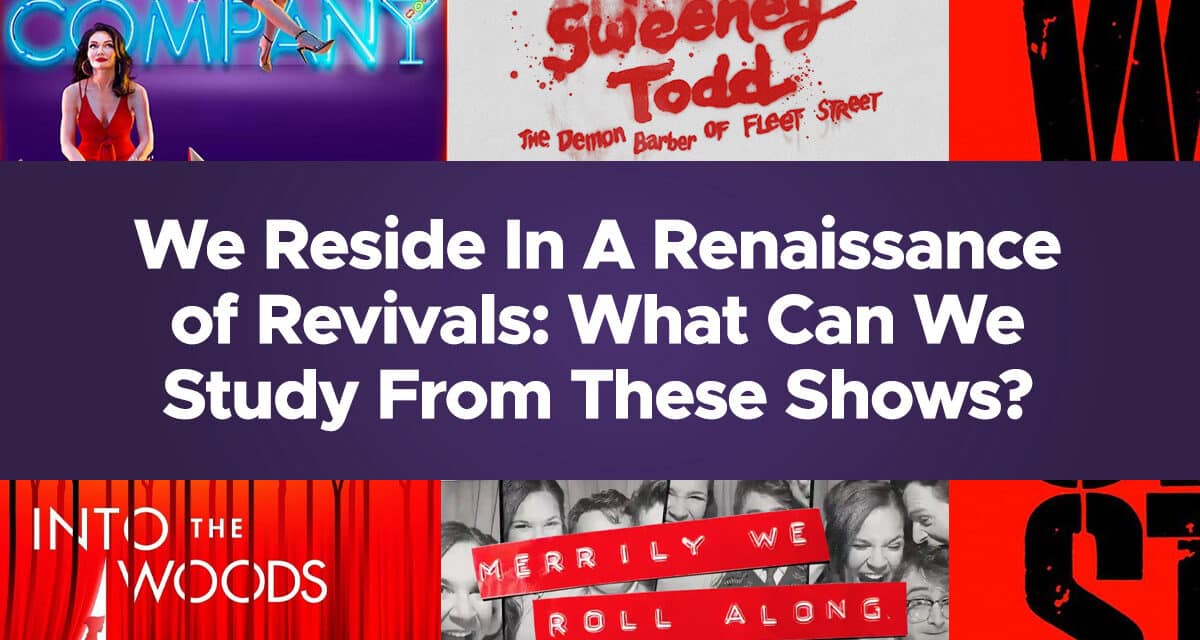

Sweeney Todd, Chicago, Merrily We Roll Along, Company, The Music Man; we’re witnessing a renaissance of highly acclaimed revivals on Broadway.

Why revive these musical theater classics? Especially in the age of streaming services, we have new dramaturgy and musical content at our fingertips. Why return to musicals of a time gone by when there’s an entire frontier of virtual viewing within our screens? Unlike literature, TV, or film, we get the unique opportunity to experience these works with fresh perspectives decades after their original presentation, which can only help us as we continually develop the craft of musical writing. It’s similar to the revisitation of historical fashion trends, like corsets and stays- musical revivals on Broadway today aren’t mere copies, but contemporary reinterpretations of their original forms. Our modern audiences can enjoy their artistic peers’ unique perspectives of a classic show in real life, not through a screen.

Where there is opportunity for interpretation, there is room to learn. Not all shows throughout history are deserving of a revival, not without at least a few crucial revisions for our modern sensibilities. However, some musical revivals prove their original work stands the test of time. We can glean many lessons from these recent revivals on Broadway, but let’s dissect the following lessons together:

- Study Your Sondheim

- Complex Characters Create Compelling Conflict

- Structure Serves Storytelling

Study Your Sondheim

A mere two years since his passing, Stephen Sondheim remains one of the most produced musical theater creators of all time. As of autumn 2023, we can enjoy critically-acclaimed revivals of Sondheim on Broadway (Merrily We Roll Along and Sweeney Todd) and two additional shows are enjoying highly successful national tours AFTER recent Broadway revivals (Into the Woods and Company).

Even if we take away those shows, Sondheim’s work in his last fifteen years of has been revived on Broadway a whopping SIX times (West Side Story, 2009 & 2020; Gypsy, 2008; Follies, 2011; A Little Night Music, 2009; and Sunday In the Park with George, 2017). As if that wasn’t enough, we have access to Sondheim’s final (and unfinished) musical Here We Are.

Therefore, it’s fair to say that Sondheim’s catalog is worth rigorous study given that his work continually receives new perspectives. Though I could go on about Sondheim, there are countless articles, essays, books, videos etc. that dive far deeper into Sondheim’s musical craft, so consider this an empathic request to “Study Your Sondheim.”

You can use this list as a good starting point for your Sondheim journey. In particular, I recommend looking at his song structure, rhyme schemes, motif developments, and accompaniments as you dive into what makes Sondheim musicals so desirable for revivals. He is unequivocally one of the masters of musical storytelling and deserves further study by any aspiring musical theater writer.

Complex Characters Create Compelling Conflict

Just as alliteration alerts the audience’s attention, so do complex characters. A hallmark of writing is to build your characters three-dimensionally. This includes (but is not limited to) a character’s desires, history, and personality. It’s tempting as a writer to keep your characters “colored inside the lines” (i.e. protagonist exudes traditionally heroic qualities, antagonist exudes villainous qualities, love interest hopelessly falls for the protagonist even though they met two scenes ago, etc.). These archetypes are easier to write and help signal for the audience who we should root for.

However, archetypes don’t always lead to compelling conflict. It’s the relatability of a complex character to the audience that makes them engage with the show from start to finish.

For example, if we take Chicago (a revival from 1996 and the second longest running show on Broadway behind only Phantom of the Opera), we have a cast of complex characters such as Velma Kelly, Roxie Hart, and Amos, each with distinct desires and methods to overcome obstacles. These complex characters lead to far more dynamic onstage relationships (and therefore conflict) on stage as the show unfolds. For example, we see the complex relationship between Roxie Hart and her husband Amos as Roxie’s dream of becoming a celebrity leads to her perjury in court and a fake pregnancy, all while Amos seeks to fulfill Roxie’s requests before finally leaving her.

We don’t necessarily need murder or shady law proceedings to create complex characters either. Take the recent revival of The Music Man which ran on Broadway from 2022-2023, specifically the character of Marian the Librarian. She could have easily been the “hopelessly in love” romantic counterpart for protagonist Harold Hill, but we watch her reveal shades of her complex character throughout the show. For example, she isn’t smitten upon Harold’s arrival, nor does she fall immediately for him after she sees how much he’s built up her brother Winthrop’s self-confidence. Later in the show, she reveals to Harold that she knew he was a fraud since the third day of his scheme, but defends Harold later on in the show since he made the townsfolk excited to play music again (good intentions or not).

By showing these complex feelings throughout the show, we get a far more compelling finale when Harold and Marian are finally united. Therefore, take this as a sign that your complex characters need time to shine their complexities; what you get is more compelling conflict throughout your show.

Structure Serves Storytelling

As 20th century architect Louis Sullivan said, “Form follows function”, but we’ll transform the saying to be more applicable to musicals; “Structure Serves Storytelling”. To be specific, the way you order musical numbers and scenes is imperative for successful storytelling.

The majority of these revivals on Broadway (with one notable exception) follow the traditional two-act musical structure, which features a typical arrangement of musical numbers (e.g. the opening number introduces us to the world and the protagonist; the “I Want” Song introduces us to the protagonist’s desire and what they’re looking for; a conditional love song between your romantic leads to spice up the romance; one or two rousing production numbers to excite the audience, etc.). For more information on these and other types of musical numbers, please see the articles below:

- Curtain Up, Light the Lights: Opening Numbers

- Five “I Want” Songs That Work

- If I Loved You: Conditional Love Songs

- “The Noise” – Production Numbers

The purpose of this article is not to dive too deep into musical theater structure, but rather to highlight that these revivals have a similar structure which audiences have clearly enjoyed for decades. Therefore, consider this an invitation to study the structure of these shows to inform your own writing; audiences clearly find this structure compelling to watch regardless of the decade.

If you DO decide to break away from the beloved two-act musical structure, it must be for a compelling reason regarding your story. For those who haven’t seen the show, Merrily We Roll Along is told entirely in reverse chronology over twenty years where we see the protagonists (Franklin Shepherd, Charley Kringas, and Mary Flynn) start in the show at the lowest point in their friendship and then end the show at their most spirited and youthful.

Hal Prince and Stephen Sondheim chose to deviate from the traditional musical structure in this instance because it helped tell the story of how friendships can evolve negatively over the course of time. However, by telling it in reverse, we’re left at the end with a hopeful message that the “end of the friendship” we saw at the beginning of the show doesn’t necessarily have to be the outcome. Had Prince and Sondheim used the traditional structure and told the story in chronological order, we as the audience would be watching these characters become bitter and disillusioned – not exactly a rousing way to end a show. Hence why if you choose to deviate from the format of the traditional musical structure in your original work, be sure to make it serve the thematic material of your work.

Final Thoughts on Studying Revivals on Broadway

We are so fortunate in this day and age to have access to so many high profile revivals on Broadway. It’s rare to witness a work reinterpreted by our artists today, so please visit live shows whenever possible. There is so much to learn from a live production that a script or recording could never reveal. The past always has lessons to teach us for the future, and I hope this gives you encouragement to go forth and learn more about your craft from the masters while we can.