Get set to “set” your lyrics!

So, you’ve written the lyrics to a song, and now you’re ready to set them to music! Let’s take a look at how to set your lyrics to music effectively using good prosody and stressing the proper syllables.

What do the terms “stress” and “prosody” mean?

When we stress a syllable, we put more weight on that syllable than the syllables surrounding it. We say, “table” rather than “table.” We say, “pretend” and not “pretend.”

These stresses apply to words in sentences as well. We say, “Break a leg” rather than, “Break a leg.”

Prosody is a bit more all-encompassing. In musical theatre, it refers to the artfulness and effectiveness of lyrics, and how they’re set to music using rhythm and pitch.

When writing lyrics for musicals, it’s often preferable to make the majority of our music sing near the rate of speech and follow all of the same stresses as if the character were speaking rather than singing.

Having good prosody doesn’t mean that the music will sound as if we’re reciting a monologue or be a perfect facsimile of speech-pattern talking. But it does mean that all of our words will have the same stresses on the same syllables we would have if we were simply speaking the lines. (We’ll talk about some exceptions later)

Why does it matter when setting lyrics?

Properly stressing syllables and having good prosody helps the audience to hear the lyrics correctly on a first listen. This is particularly important in musical theatre, where audiences cannot re-listen to a song at their leisure during the course of the story. In musical theatre, lyrics often contain important information that will affect the rest of the story so it’s critical that audiences don’t miss any lyrics!

Additionally, you never want your audiences spending any of their brain-power trying to decipher mis-accented lyrics, or thinking, “Huh, that doesn’t quite sound right.” Just like our actors stay in-character, we want the audiences to be completely immersed as well.

Learning stress and prosody from the greats!

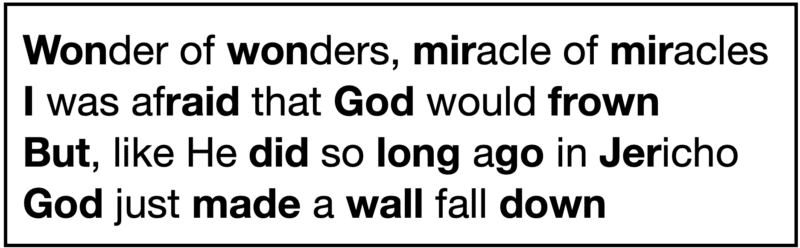

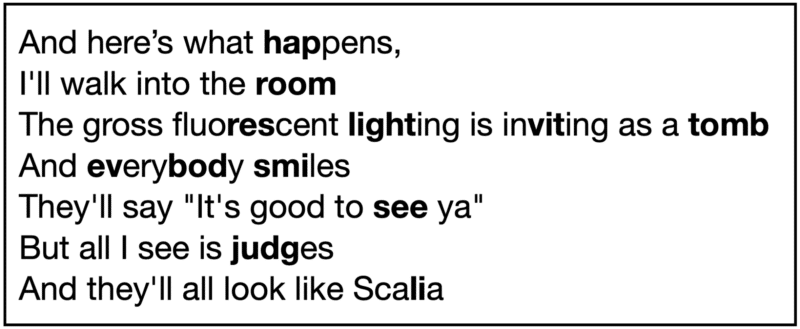

Let’s take a look at some well-set lyrics and see if all of this theory holds up!

For each of the excerpts below, speak them aloud as a monologue and then listen to the recordings of the songs. The stresses should all line up roughly how you spoke them.

“Miracle of Miracles” from Fiddler on the Roof

(music by Jerry Bock, lyrics by Sheldon Harnick)

“How Can I Call This Home” from Parade

(music & lyrics by Jason Robert Brown)

“I Know What’s Gonna Happen” from Tootsie

(music & lyrics by David Yazbek)

Notice how all of the stresses remained on the same syllables and the words had roughly the same weights, both in your spoken renditions, and in the recordings!

Proper scansion is also a way to make our characters seem authentically human. If characters frequently sing in a non-speech pattern way it makes them seem less like real human beings. Poor prosody is the musical equivalent to wooden dialogue!

How do you stress a syllable?

There are two ways we can stress a particular syllable when setting lyrics. One is with rhythm and the other is pitch. Rhythmically, we can make a syllable land on a “down beat” or “strong beat.” In 4/4, beats 1 and 3 are often the strongest beats, but beats 2 and 4 are also relatively strong beats.

But maybe you’re forced, for one reason or another, to put what should be the stressed syllable on a “weaker” beat. We can make that syllable’s pitch higher than the surrounding notes to give it a little more “weight.”

Let’s take a look at a hypothetical passage, first set correctly, then incorrectly. Since we’re in 6/8, the strongest beats are “1” and “4” if we’re counting “1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6″ or beats “1” and “2” if we’re counting it as a compound meter of 2 beats, as in, “1 & a, 2 & a.”

Bear in mind there’s no one right answer, this is only one proper setting of the lyrics.

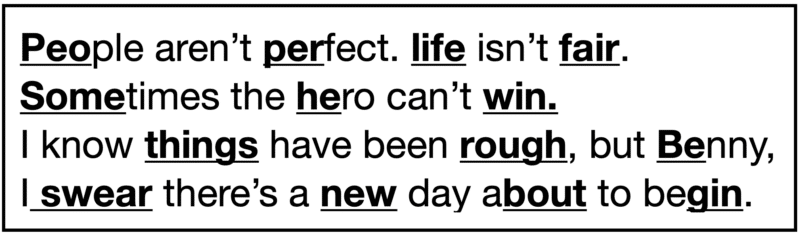

Correctly stressed when spoken:

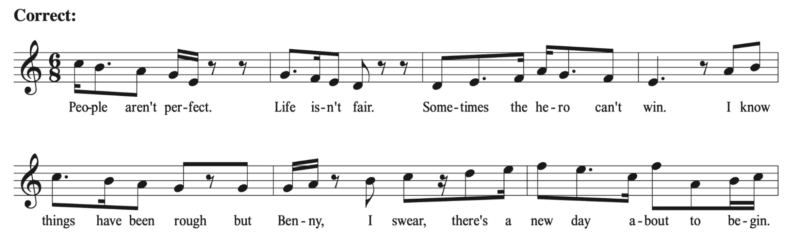

Correctly set to music (listen using the audio player below the score):

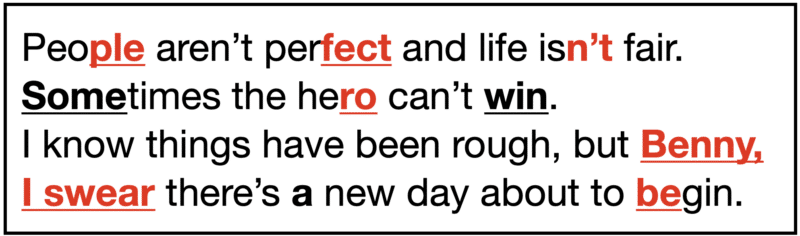

Spoken with some incorrect stresses, marked in red:

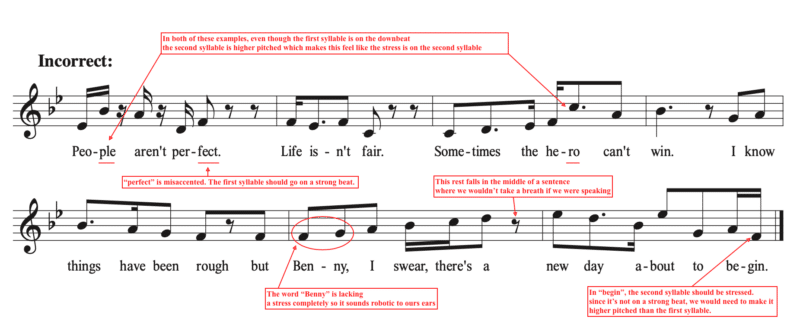

Incorrectly set to music:

Tongue twisters

Watch out for accidentally writing a tongue twister! The kind of tongue twister that comes up most frequently in lyric writing is the kind where our tongue is not in position to sing the next syllable. Let’s take a look at a hypothetical example. Say the following out loud:

Did you catch the tricky part? “… and at last take the wheel.” The back-to-back “t’s” are almost impossible to say smoothly, if you’re truly aspirating both “t’s”. Sometimes this doesn’t really matter. Your performer might just sing something that sounds closer to,“and at lastake the wheel.”

You’ll have to use your ears to decide if this vernacular way of singing works for the character and is decipherable to the audience. If it’s not acceptable to your ears, you’ll either have to change the lyric or change the rhythm so that there is space between the two “t’s.”

Tempo and rate-of-speech in lyric setting

Prosody isn’t truly tied to tempo or our character’s rate of speech but it’s worth keeping in mind that tempo should be tied to emotion. If your charter is in a flurry of emotions that might necessitate a higher tempo. If your character is in an introspective moment a slower tempo would most likely be more appropriate.

Let’s take a look at “One Hand, One Heart” from West Side Story (music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) which has a rate of speech that equals approximately fifty five syllables per minute. This slow rate of speech makes the moment seem tender and intimate. Notice how the syllables are still properly stressed despite a slower tempo.

Good prosody works at just about any tempo. If you have a passage of lyrics that feel difficult to sing at tempo it’s possible that it might be too fast but more likely, the syllables are working against you.

Let’s take a look at some examples of some high rate-of-speech passages.

“Washington On Your Side” from Hamilton (music & lyrics by Lin Manuel Miranda)

“Not Getting Married” from Company (music & lyrics by Stephen Sondheim)

Melismas, Riffs & Runs

A melisma is when we have one word stretched out among multiple notes. It’s important that even when a lyric is melismatic it still has the proper syllable accented. In modern lingo, we usually say “riff” or “run” instead of “melisma” unless it’s a rather unexciting melisma. “Run” or “riff” usually has a more exciting, showy, connotation than “melisma.”

Melismas are often used as a way of heightening the emotion of a particular word. If the song is one of grief, a melisma/riff can be a form of keening. If the song is a celebration, it’s a kind of celebration.

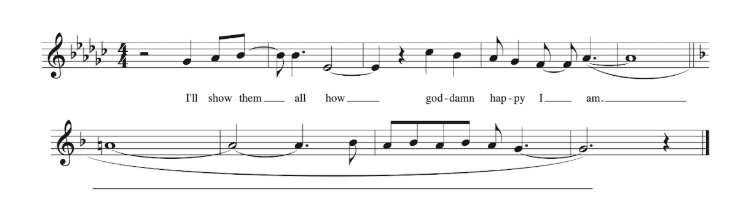

Melismas can also be about being “performative” even in a non-diegetic way. In “What Baking Can Do” from Waitress (music and lyrics by Sara Bareilles) Jenna sings the following with a held note and then a riff on the word “am.”

The riff is performative; Jenna is actively trying to show the world how “happy” she is. (Spoiler alert, she’s not.)

Who is responsible for making sure lyrics are set effectively?

If your team is taking a “music first” approach in your songwriting process, meaning the composer is creating the melodies before the lyricist writes lyrics to accompany those melodies, the lyricist should be mindful to create lyrics that sit in the melody with the correct stresses.

If your team is taking a “lyrics first” approach then it is the composer’s responsibility to set the existing lyrics effectively.

Usually, regardless of the approach, there is a give and take between lyricist and composer to create well-set lyrics!

The exceptions to the rule

There are exceptions to every rule, and here are a few examples of when we might want to incorrectly stress words for effect:

Exception 1: diegetic songwriting

If the song is diegetic, meaning the song is happening in-world, incorrectly accented lyrics can actually reveal something about the level of song-writing craft a character has.

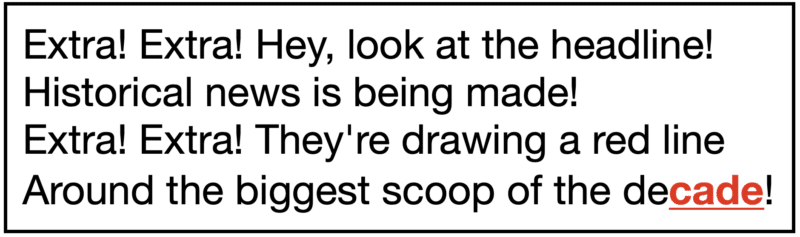

For instance, in “Baby June and her News Boys” from Gypsy (Music by Julie Styne, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) Baby June and company are performing a song that was written by the character of Mama. The song contains this obvious incorrect stress:

This incorrect stress signals to the audience that, while Mama is driven, she may not have the same talent and proficiency of a trained professional.

Exception 2: Playfulness

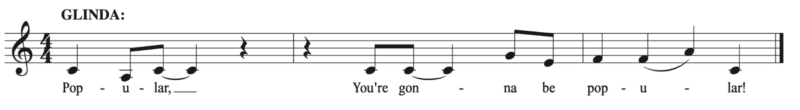

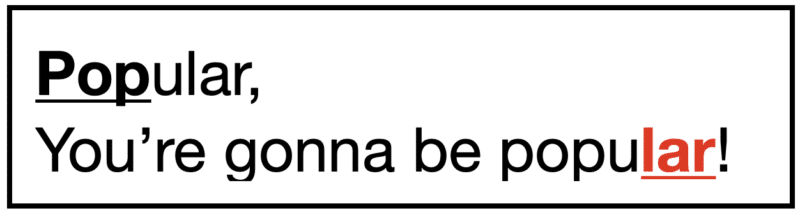

If your character needs to exhibit a certain amount of playfulness or excitement, playing around with a word can be a great way of achieving that characterization. Let’s take a look at Popular from Wicked. (Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz)

In lyric form, that looks like this:

Importantly, we hear the word “popular” correctly the first time which acclimates our ears to the word before Glinda plays around with where the stress is placed. This helps to achieve a very bubbly quality to the lyric!

In Conclusion

Now you’re ready to properly set your lyrics to music in a way that is both artful and effective! Remember to always sing your lyrics out loud. This will help you catch any improperly accented syllables quickly and easily.

This article is the 3rd in a series of articles by guest writer Sam Sultan on songwriting basics. Make sure to check out Part 1 – Finding the Form, and Part 2 – Perfecting the Perfect Rhyme for more great tips!